Scotland's Footballing Eras

- the stats and facts of four Golden and the Rest

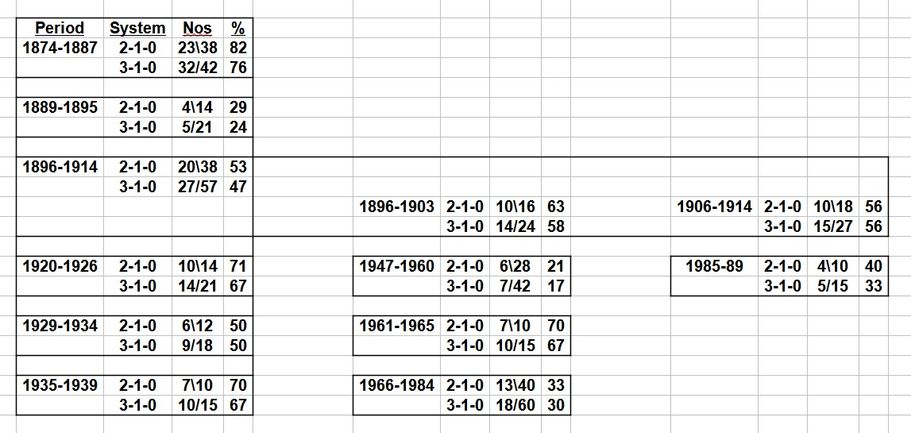

A very good team might be expected to win its home games and draw away. That is over ten games five and five so fifteen points over a possible twenty or 75% under the old 2-1-0 system or 67% under the present 3-1-0. Thus an exceptional team would by definition post better percentages, a a poor one less with an average one 50:50. So in terms of Scotland-England encounters, the game that for much of the history of Scottish football, particularly in the hundred years from 1883-4 of the British Home Championship, has mattered the most, there are two periods, three eras, when it was 33% or less, so very poor, one when it was just poor, one when it was average, two when it was better than average, two when it was very good, "golden eras", and one when it was exceptional, i.e. "burnished gold".

Worst of all at under 20% was the period from the restart of the game after World War II to 1960 with the reason for what can only be described as abject failure on the face of it something of a mystery. The England team of the same period was also nothing to write home about as its results against "foreign" opposition that mattered show. In fact both teams were restored only with the introduction almost simultaneously of real football men, Alf Ramsay, and for us, with a subsequently exceptional points-ratio touching 70%, the in terms of injuries very unlucky and thus much under-estimated Ian McColl.

But neither McColl/Ramsay's era, nor the period before or that after them from 1966 to to the abandonment of the British Home Championship in 1984 with at best 33% and then the five years of the Rous Cup with 37% or so are ones, which concern us at SFHG. We leave them to the Scottish Football Museum to explain, instead, as ever, concentrating our efforts on pre-1939 with just the 25% from 1889 to 1895 problematic.

However, even for that period there is perhaps a reasonable explanation, or at least a confluence of circumstances, three in all. First, in 1888 the Renton Revolution had just burst onto the scene and would have its impact on the Scottish and then the English games but not instantly and not without birthing pains; as the 0-5 defeat of Scotland at Hampden in 1888, after sixteen seasons England's first ever away-victory, would demonstrate. James Kelly was centre-half and held his man in check but there were clearly problems down the right-side of defence, where Queen's Park and therefore old-style and Arnott and Renton and new-style Kelso did not gel. And it was a problem that seems to have reoccurred in 1893, notably with now an ageing Wattie Arnott still at full-back, and even continue a little beyond.

Second, there was the creation Down South, also in 1888 and by a Scot, William McGregor from Perthshire, of the Football League, based on the Middle and North-West England. With it came an almost instant pressure and some ability to pay for better players, its adding of clubs, then a division and more clubs still and eventually in 1894 yet more with the southern English response in the form of the Southern League only increasing the demand. In 1887 there had been 80-odd Scots known to be playing in English teams. In 1890 there were more than twice as many, in 1893 three times and by 1896 the number had touched two-hundred and fifty. It had meant some of the cream and much of the emerging, younger talent was, with its residence rule, being rendered ineligible for the Scottish National team and it very quickly showed.

Third, the home Scottish game became uncompetitive. The Scottish League only started, indeed was almost forced as a reaction to South of the Border to start, in 1890-91 and official professionalism not accepted until 1893. And, whilst they to a degree stemmed the outward flow, the real breakthrough internationally came when in 1896, after the country's team had been 3-2 down to Ireland until the seventy-eight minute with the England match next, the SFA bit the bullet, the residence qualification being dropped and Anglo-Scots finally accepted for selection. Five were chosen. They included for the first time the nation's recognised best centre-half, James Cowan, previously of Renton and now of Aston Villa. And Scotland went on to win 2-1 in front of a record 50,000 plus crowd.

However, even with Anglo-induced revival Scotland was truthfully to be returned to little better than an average team. From 1896 to The Great War the infernal ratio was only between 47% and 53%, albeit that it was suppressed by two dips, first, as at the turn of the century Alex Raisbeck was found as a replacement for Cowan and in turn between 1903 and 1906 Thomson for the Anfield maestro. And this suppression by succession was to be repeated in the early 1930s but with a further twist. The game was changing, at least in Britain, and with the introduction of the centre-back, moving away from both the Scottish centre-half and Pyramid models. At Ibrox specifically and therefore, at the time, also for Scotland 5ft 8ins Davie Meiklejohn was replaced by 6ft plus Jimmy Simpson but with effect. Scotland's ratio, in a brief golden era, rose to the outbreak of the Second War not just to two-thirds but almost exactly the same as it had been immediately after the First.

At that time with hostilities over, from narrow defeat 5-4 in the 1920 international despite away being 2-4 at halftime (Alex McNair, the ageing Scottish right-back and captain at thirty-five seemingly running out of legs), Scotland for the rest of the next decade went on an extended run that would include a surprise home-defeat in 1927, the 1928 Wembley Wizard response and be based on five attacking players of exceptional qualities - initially Andy Wilson and Alan Morton, then the Alexes, Jackson and James, and the Gallacher, who was eligible, Hughie. His namesake, Patsy, Scots-raised, buried and even featured in the Scottish Football Museum, but just Irish-born and perhaps the best of them all was not so.

And that takes us back finally almost to origins of the game, at least North of the Border. After the tactical and organisational innovations of 1872's initial international and the first-ever failure of blending the following year, an experiment never repeated - the problem being the incompatibility of Scots players with Diasporan ones - Scotland was in the next fourteen seasons to defeated only once; in London in 1879, from a winning position and in controversial circumstances that, shall we say, today might trouble VAR. The outcome would be an extraordinary ratio of 80%, one that should be the object of a great deal more national pride than is the case. It might even to be said to have made the game, not least by effectively largely sweeping aside globally the Rugby alternative, and deserve perhaps if not a museum of its own then full-coverage, missing thus far in what we have.

Back to the SFHG Home page