The Scots in Argentine Football

(or How It Really All Began)

(This article was in its original form first supplied in March 2025 on request to CIHF, Argentina's Centro para la Investigacion de la Historia del Futbol)

Before any serious analysis of the role, the pivotal role Scots played in the bringing of Association football to Argentina, indeed more widely in Latin America, two points of the utmost importance have to be made.

The first is that, whilst the United Kingdom is a state with a single monarch, it is not a country or a nation. It is made up of four distinct parts, four actual countries, each with its own culture, indeed, language, even languages. Those countries are England, Scotland, Wales and now Northern Ireland, which until 1920, so during the era of the transmission of football abroad, was the whole of the island of Ireland.

The second is that the British Isles, as we might for our purposes better call the United Kingdom, are class-riven, the distinction between the upper- and lower classes being based not only on money but also history with England having first invaded, conquered and subsequently appropriate much of the wealth of Wales, then Ireland and finally Scotland, specifically Northern Scotland. This is important in the Argentine context because of the invasions of the River Plate region, notably Buenos Aires, in 1806-7 were by the British establishment, the upper classes, as part of an attempted wealth-grab, whereas football was brought to your country by the working-classes in both the capital, in Rosario and elsewhere. Colin Bain Calder was a carriage-painter, whose father was a carpenter. Alexander Watson Hutton’s parents were shop-keepers in one of the poorest districts of Glasgow, Alexander Lamont’s father was probably a carter and the Leslies were plumbers. None was born to wealth. All migrated to Argentina to improve their lives by hard work, as did the mainly Spanish and Italians, who would also arrive over the same period from 1880 to the beginning of the First World War. In fact one of the very few differences between the arriving Scots, Spanish and Italians was that the first already had the football contagion in their blood and the others did not; at least not yet. In Italy, whilst football arrived from 1899, the working-class game took another decade. In Spain it began in 1878 with the foundation, incidentally by Scots, of Rio Tinto F.C, followed in 1889 by Recreativo de Huelva, founded also by Scots, but did not take off until the first decade of the 20th Century.

So at this point a short history of football in the British Isles might be helpful. In Scotland we are very careful to make the distinction between “foot-ball”, “football”, which, for example, includes rugby, and “Association Football”, i.e. “Soccer”. In parts of our country “folk-foot-ball” has been and remains a traditional past-time for as long as people can remember. In our Scots language we call it “fitba”. It was played within and/or between villages and within towns, involves a ball, and took two forms. One, still played in particular locations, had and has little actually to do with feet, has no limit on numbers per team and few rules. In Western and Northern Scotland we also have a second field-game, which is called shinty, is the origin of ice-hockey, is also still widely played and was, before “soccer” even more widely enjoyed. And in Southern Scotland we also have concrete evidence of football played on a smaller scale. Earlier this year, 2025, a piece of round in Anwoth in Dumfriesshire has been scientifically confirmed as the currently-known, oldest football field in the World.

Moreover, in England “foot-ball” was played too, of the “folk variety, in the upper class schools, e.g. Rugby, of South and Middle England but also from 1857 in working-class areas of North England, notably Sheffield. As a result codes for playing the organised game emerged. Cambridge was one, Sheffield, as very much a kicking-game, another with, in 1863 from London, the Football Association (FA) the “Association” rules being one of the last. They were created by clubs that again did not want to play what were essentially a hand-ball game, an early rugby, but were confined in origin to teams from the English capital and the countries around it.

That is until 1871. In the winter of that year one Scottish “football” team, middle-class Glasgow’s Queen’s Park (QP), agreed to accept the London “Association” rules in full. It then allowed QP not only to play in the newly created London competition, the FA (Football Association) Cup, but to reach the semi-final.And that was the trigger, initially, for the first official, international match, held in Glasgow in November 1872, then in Scotland specifically for clubs to be formed rapidly, some also middle-class but for the first time many working-class, and, finally, for crowds, again both middle- but increasingly working-class, to come to watch. By 1875 there were over two hundred and fifty football clubs in Scotland, forty-nine took part in the newly-created Scottish Cup compared to thirty-two in that year’s English FA Cup. Moreover, 10,000 spectators came to watch the 1875 Glasgow-Sheffield inter-city encounter, the same number coming to the 1876 Scottish Cup Final as against 3,500 for the English equivalent.

Thus it was at about this point in time it became clear that in Scotland Association football had already become a full, societal passion, whereas in England it remained segmented by class and location, something which only began to change with the subsuming from 1877 of the Sheffield- into the Association-game albeit with several of the former’s rules being incorporated into the latter.

And the distinction between Scottish and English football even on-field, showed from the beginning. In the first football international the Scottish team had introduced the concept of tactics and most particularly coordinated defence. It had played 2-2-6 (2-2 being essentially a shinty formation), whilst the English with 1-1-1-7 more or less just attacked Moreover, whilst England for a decade chopped and changed Scotland continued with the same shape to 1887, in doing so winning all but two of the encounters in-between, both losses away and in special circumstances. Indeed Scotland would in the same period also be undefeated against Wales from 1876, against Ireland from 1884 and begin to export players to English clubs. The first had already gone in 1876, seventeen were known to be there by 1880, by 1884 it was seventy-four and in 1888 when the English Football League was founded, by a Scotsman, one hundred and fourteen.

And this was also the period when Scotland, Glasgow in particular, was the heavy industrial capital of Britain and therefore the World, with most prominent amongst those industries ship-building and, in the North and Latin American context, railways. It meant Scotland required the import of materials to feed its factories, with Scottish merchants abroad at the forefront of sourcing them, and Scottish expertise was in demand globally, with South America no exception, to build civic and industrial capacity and transport infrastructure.

So it was in the specific case of Argentina that when Alexander Watson Hutton (AWH) arrived in Buenos Aires (BA) in 1882 he did so to provide education directly for the children of Scottish merchants as well as others. St. Andrews, St. Andrew being Scotland’s patron-saint, was a “kirk”, a Church of Scotland School. It was and remains Presbyterian. It is not Church of England. And, as a Scot born in 1853 so twenty as the game exploded in Glasgow, a “soccer” city, and then living in Edinburgh with its mix of the rugby and Association, AWH was aware of both codes, as his later life in Buenos Aires would demonstrate.

It meant that when AWH was able in 1884 to start his own school, the English High that was probably designed to offer more highly-regarded Scottish-style education to a wider pool of British immigrants beyond the kirk, he was also able to place Association football on the curriculum, introducing it for the first time but for the moment only at junior level to his adopted country.

Now here some historians might point to the Buenos Aires Football Club, to which I reply, “look to the timing and the definitions”. Whilst there is no denying that that the often cited game played in 1867 was “football”, despite it being post-1863 there is equally nothing to point to it being Association rules. In fact there is every evidence to the contrary. And that leads us in Scotland to the conclusion that, whilst the role of Watson Hutton should not be diminished, for the first, real appearance of senior, if you like fully “adult” Association football we have to look not to BA but Rosario.

Colin Bain Calder, a carriage painter to trade, arrived in Argentina at some point after 1881, when he was still living in his home-town of Dingwall in the North of Scotland. Fitba was a game played locally. Association football arrived in the region from 1877 onwards, when he was seventeen with him clearly bitten. And when by 1889 he was managing the paint-shop of The Central Argentine Railway Company in the country’s second city it was again he who advocated for company club to play to Association rules and no other. And to those rules, with him as its first President remaining in place for over a decade, the club has remained true to this day, still playing, as you are aware, as Rosario Central in the country’s top flight.

And it was perhaps the Rosario spark, augmented by the efforts of George Robb, also a Scot and a teacher, which in 1891 caused a true awakening now in Buenos Aires of the senior game. It is noted that in 1888 a Southern Railway Athletic Club team, playing out of Lanus, the location at the time of the Southern Railway’s yard, seems to have taken part in friendlies mostly against English High School with Alex Watson Hutton involved with and in both teams, which were a mixture of senior and junior players. But fully senior Association football seems to have arrived in the capital in 1890/91 with the first Argentine Association Football Championship. Taking place in the Argentine winter of 1891 the competition consisted of six teams, one of which in the end did not take part. It was on a league basis, a concept only introduced even in England in 1888, and by the afore-mentioned Scot, William McGregor. It was under the presidency of F. L Wooley, with board-members Rovenscraf (probably Ravenscroft), Arcels, Hughes and three probable Scots, McEwen, McIntoch (Mc or Mac being the Gaelic for “son of”) and Alec Lamont, the Secretary and of whom more later. And it finished with two clearly Scottish teams, Old Caledonians and St. Andrews,, Caledonia being the Latin for Scotland, on the same number of points, each with six wins, one draw and one loss, although the former had a far superior goals difference, +21 to +11.

Under normal circumstances it might have meant that Old Caledonians would be declared Argentina’s, in fact really Buenos Aires’s, first football league champion. But the situation precisely mirrored the outcome of the first-ever playing of the also new Scottish League six months earlier. There Dumbarton and Glasgow Rangers had finished on equal points with the former having the somewhat better goal difference. Yet the decision was for a May play-off. Moreover, the Argentine league, with very strong and reasonably fast links (two weeks by boat) between the Diaspora and the homeland, by the time of its termination would have been aware of these events. In fact there is a good case to be made that the creation of the Scottish League in 1890 may have been one of the main drivers, given its Scottish core, of its Buenos Aires equivalent.

Thus Old Caledonians and St. Andrews too decided on a play-off and unlike Dumbarton and Rangers, which had drawn theirs, agreeing to share the trophy, St. Andrews, with Alex Lamont at centre-forward and beside him John Caldwell, who had played for senior club Partick Thistle in Glasgow, emerged the winner, with a hat-trick from Charles Douglas Moffatt. Note here that Moffat is a town in southern Scotland and Douglas, in Gaelic, spoken in West Scotland and Ireland, means black-grey.

It then seems likely that 1892 would have followed much the same pattern as 1891 but for the death of President Wooley. So, instead, between the clubs, with several disappearing and new ones joining, friendly games were played, which involved just two of the previous year’s teams but also six new ones with Lomas Athletic Club, a sign of the future, the pick. It was “managed” by Arnott Leslie Jnr., the eldest son of a Glasgow-born plumber, and would include two of his other sons, George and William, teenagers recently returned from their Glasgow, Scotland school.

However, under again the secretarial guidance of Alex Lamont again, in 1893 the Argentine Football Championship rose once more. By then of the original clubs only Buenos Aires and Rosario Railway, not from Rosario itself but Campana to the north of the capital remained, to be joined by two teams from the newer, railway suburbs to the south, Lomas one of them, and just two from the old city itself. The first was Flores and the second English High School, with Alex Watson Hutton, despite the imminent death from cancer of his first wife, also Scottish-born, probably persuaded by Lamont, and the Scottish connection to take on the Presidency. It was a master-stroke, a first of his life-saving gifts to Argentine football, and not because the game immediately boomed. It did not, not least because the man who might otherwise have taken the administration of it on his shoulders, Alex Lamont, in April 1894 left the Argentine initially for Brazil and ultimately we believe but do not have complete proof, for Scotland and then South Africa. But it did begin the process of holding the game together until a decade later boom did take place.

In fact, Watson Hutton’s English High was to re-join what is ow known as the Argentine Championship for one season only and in 1895 and 1896 it was, led by Lomas, down to just five clubs. But the league survived with AWH still in place until 1896, the addition of Belgrano, the sports-club where he was also member and a future president perhaps critical.

But it was not to be easy. Whilst under the two year presidency from 1897 of Alfred Boyd the league would see a welcome increase in number to seven, with the Scottish presence of Lomas and the Leslies continuing to be the gold standard. However, under Charles Wibberley in 1899 the number fell to just four albeit now with a Second Division, and would remain so in the first two years of the stewardship of Frank Boutell. Indeed, but for the re-emergence in 1900 of a Watson Hutton English High School cum Alumni team, his second life-saving gift to the Argentine game, and the joining that same year of new team British-based team, Quilmes, that number would have been two with the league quite possibly simply folding.

However, it was perhaps that teetering on the edge of disappearance that finally seems to have concentrated minds, aided by the parallel development of the game across the River Plate in Uruguay. Representative teams from Buenos Aires and Montevideo had first faced each other in 1892 but not since. Then the former had won 4-1. But in 1901 essentially that fixture was revived as a mainly Albion F.C. team from the Uruguayan capital played an Argentine capital select. Both the Leslie brothers were in the latter, winning eleven and it was captained by James Anderson, like them Argentine-born but another with a Scottish father. And this pattern was repeated indeed reinforced, when the following year the two countries met officially for the first time. Anderson was captain once more. William Leslie played at right-back. There were two Buchanans and also two Browns, very much still Diasporan despite being the great grand-children of Scots, who had arrived from The Scottish Borders in 1825.

Eight thousand are said to have watched that 1902 match, played in Montevideo but a 0-6 win for the visitors. And when the return fixture took place the following year in Buenos Aires, incidentally won by Uruguay, the crowd was a healthy 4,500 and the game seemed to have turned a corner. The number of teams in the league, dominated by Alumni, had recovered to six, would be seven in 1905 and, as Boutell stepped down, eleven in 1906. Moreover, for the first time the new teams joining were non-Scots, indeed non-British and there was for the first time soft sponsorship. The Tie Cup in introduced in 1900 by Boutell was supplemented from 1905 by the Copa de Honor Cusenier and the Copa Lipton. This last was gifted by Sir Thomas Lipton, the Scots grocery millionaire also from Glasgow, who had started life in the same low-class district of the city as Arnot Leslie Snr, Arnot Jnr., William and George’s father, and Alex Watson Hutton, indeed who himself is said there to have played the pre-Association game in the 1860s.

And here is perhaps the first of the most important facts that current Argentine understanding of its football history has to revise. The British, who had arrived in Argentina in increasing numbers in the 1880s had been brought up as a minimum with football, alongside cricket and rugby, as at least a sporting interest. Yet for the many Scots amongst them, it making no difference if you were middle- or working class, it was a passion. Moreover, it was, if anything even more so for the again Scots but now working-class ones, who arrived in the 1890s to build your sewers, your railways and other infrastructure. They too had the contagion already in them, but now it was a passion their grandfathers before them did not have but their fathers did. But that was not the same for the immigrants, who came over the same period from Spain and Italy. They came with no understanding of and therefore no passion for football whatsoever. It had to be learned and it would be not them but their children, the next generation, that did so with their knowledge of and passion for the game only able to emerge with their maturity from 1900 onwards. Moreover, that learning and that passion could only come from one source, the people who lived alongside them and already had it, i.e. largely we Scots, with the conclusion being that without us – Watson Hutton, Robb, Calder, Caldwell, Lamont, the Leslies, the Browns, Anderson and others – Argentine football could not have developed as it did and modern Argentine football by definition would not exist as it does.

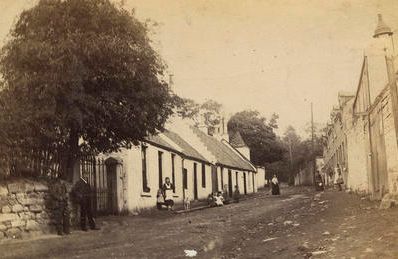

And that leads us very neatly to the second of the Scottish facts that Argentine football history needs to assimilate. The Scots, indeed also our brothers the Irish, who came to your country at very much the same time, were not rich. They were not, repeat not of the same ilk as the invaders of 1806-7. They came, it is true, looking to be paid well or for a better life but they did so from poverty. Here is a a picture of the houses, in which John (Juan) Harley, El Yoni, was born, where he lost his mother as a baby and before he was able to become a railway-man in Glasgow and then footballer first in Argentina and then in Uruguay, where his family remains to this day.

The houses are little more than hovels, no different to ones in a Galician mountain-hamlet or a Calabrian coastal village, the point being that Argentine football did not start to become “crillo” from 1905. The notion is a fallacy. Indeed, it was already Scottish crillo, “escrillo” from its very first days. Colin Bain Calder, after his father’s death, grew up in a “poorhouse”, a building for the destitute. Alex Lamont probably grew up in rural poverty and AWH, Arnott Leslie and even Sir Thomas Lipton were born and/or grew up in an area of Glasgow that was so appalling that not only has it had to be torn down and rebuilt not once but twice but its name “The Gorbals”, to this day implies grinding poverty and incipient sickness.

But back to the football narrative. Whilst Argentine, non-British, non-Scottish football began to emerge, a Third Division having been added in 1901, within the British, Scottish game there were clearly problems developing. One was simply population. Emigrants from the British Isles were not in numbers coming to Argentina or, indeed, to South America more generally. They had been going instead to Canada and were going to the USA, to Australia and New Zealand. And, as a result, Association football was taking off in all those countries. Second was the Crillo Fallacy, where to seem “ingles” became a problem, despite being actually “escoces”. And the third was the falling out of love with the game, at least the perceived increasing involvement of money and argument in it, not least by the man, AWH, rightly credited with making possible much of what was now being built upon. His withdrawal of support for Alumni in 1911 had an almost instant effect, the team ceasing to be in 1912, the club dissolving in 1913. And whilst Belgrano continued in the league until 1916 and to play football to 1926 it gradually moved its concentration to rugby, where it remains just now.

However, Scots involvement with football did not cease with the disenchantment of AWH. In fact it was to make one final and decisive intervention. It came with the election and presence for six years as President of the AFA of Hugo Wilson. He is a man seemingly ignored in his native country but again crucial, for it would be Wilson, in precise parallel to fellow Scot, Andrew Gemmell, in Chile, who completed the transfer of the administration of the Argentine game finally to non-British control.

For a season in 1906 the AFA had been in the hands of Florencio Martinez de Hoz. From 1915 it would be Adolfo Orma but from 1909 to 1915 Wilson was the man at the helm. So who was he?

Hugo or Hugh Wilson was born in Argentina in 1873. His father, also Hugh, had been born in 1845 in Scotland, most likely in Mauchline in Ayrshire, from the year of his birth an early hotbed of our football but described as having “wretched, little dwellings”. And Hugh Wilson Snr., Hugh McCrae Wilson, seems to have been another to have had a hard beginning to life, another “escrillo” story.

His mother was probably Jean McCrae. He was therefore born illegitimate, his father named as Robert Wilson. But both his mother and father appear very quickly to have disappeared and with perhaps with no living parents he seems to have been raised by his grandmother. He was thus poor with no status and little to keep him in Scotland. Therefore, whilst at fifteen he may have been in the home-village and a “Snuff-box Marker”, by age twenty-five he had found his way to Buenos Aires and there had met and married a girl, Janet (Juana) Ritchie, born in Scotland just fifteen kilometres. from where he had been. In Argentina the Ritchies were farmers in Magdalena. However, in 1843, when they had left West Gates by Kilmarnock, Juana aged two, the father had been an agricultural labourer. In that he paralleled the Browns, twenty years earlier, in being literally “dirt-poor”.

Hugh and Janet were to have two sons, Andrew, born in 1870 and Hugh three years later, both in Buenos Aires. And both boys, Hugo Snr having died in 1893, would in 1895 be living with a Ritchie cousin still in the city, Hugo described as a “business-man”. However, by 1902 Hugo was married to again Argentine-born Ines or Agnes Slamon. She was clearly of Irish origin, from Lobos and it seems likely that they had met there. Lobos’s 1898 team included amongst the forwards an H. Wilson.

Hugo Wilson Jnr. and Ines would have the first of their four children in 1903, he recorded variously as a Merchant, a Manufacturer and finally as a Diplomat, travelling to and from the United Kingdom; in 1898, 1902, 1910, 1914, 1919 and more before his death in 1940 to be buried close to others including AWH in the British Cemetery.

And diplomat he would certainly have had to be to negotiate his way through what would be first two calm and then four difficult years in office as AFA President. In 1911 an Intermediate Division had been quietly added, so four in all. However, in 1911/12 and just as affiliation to FIFA was also achieved the rival Argentine Football Federation (AFF) was formed, taking teams from the AFA’s First and Second Divisions. As a result the former was reduced to just five clubs and the number of divisions overall by one. Then in 1913 both leagues ran a remarkable four divisions once more with now fifteen and ten clubs respectively in their top flights and in 1914 it was much the same. That was before, with no doubt considerable Wilson-input, reconciliation in 1915, with combination and three divisions but a slightly crazy twenty five clubs in the top one, which was reduced to twenty-two in 1916, twenty-one in 1917, twenty in 1918 before in 1919 there was yet another spat, this time openly about shamateurism, unofficially paid-amateurism.

But by this time, as the AFA had officially ceased to be English- and become Spanish-speaking, although Wilson had as an “escrillo” of course been bi-lingual, finally there was no “Scot” there to step in to channel wise words and sage precedent from the “Auld Country”, particularly as this was an argument that Scotland had already experienced thirty years earlier. Precisely a generation earlier Caledonia had brought Argentina not just football but our “Scottish” game, then shown and taught it how to play but at that point, with Britain additionally drained by the First World War, the moment had been reached to move on. And that is what we in Scotland have done, although with, hopefully in part through this paper, now perhaps an important part of both South American and European football history, previously certainly misunderstood, perhaps even in part distorted, corrected for the sake of nothing if not simple accuracy.

Back to the SFHG Home page