A New and Scottish Historiography of Association Football

(1860-1900)

Conclusions

1) Without Sheffield for the first decade there would be no Association-football.

2) Without Scotland and the Scottish-Game for the next three decades Association-football would not exist in the present form and not as a global sport.

3) Whilst Glasgow's Southern Suburbs were the source of Association-football in Scotland and they remain, although not necessarily to the greatest advantage, the administrative centre of the same, they were not that of the distinctively Scottish-Game.

4) The source of the Scottish-Game and therefore the Scottish passing-game was Dunbartonshire's Vale of Leven.

5) Working-class football and the first working-class footballer originated in Sheffield

6) Working-class Association-football originated in Scotland, closely followed by Birmingham and North-East Lancashire.

7) Professional Association-football also originated in Birmingham and North-East Lancashire

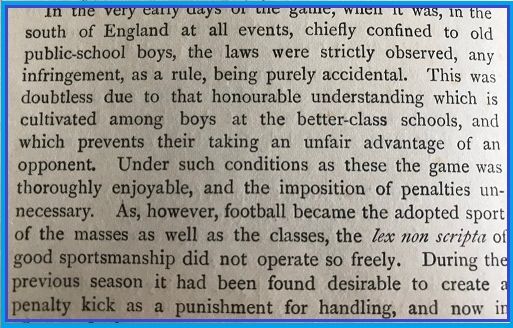

8) In England the basic driver of professional football was the administrative take-over from the game's non-Public School, middle-class founders by the products of those Public Schools, the working-class reaction to it and the import of Scottish talent over the next decade and half to fuel that reaction.

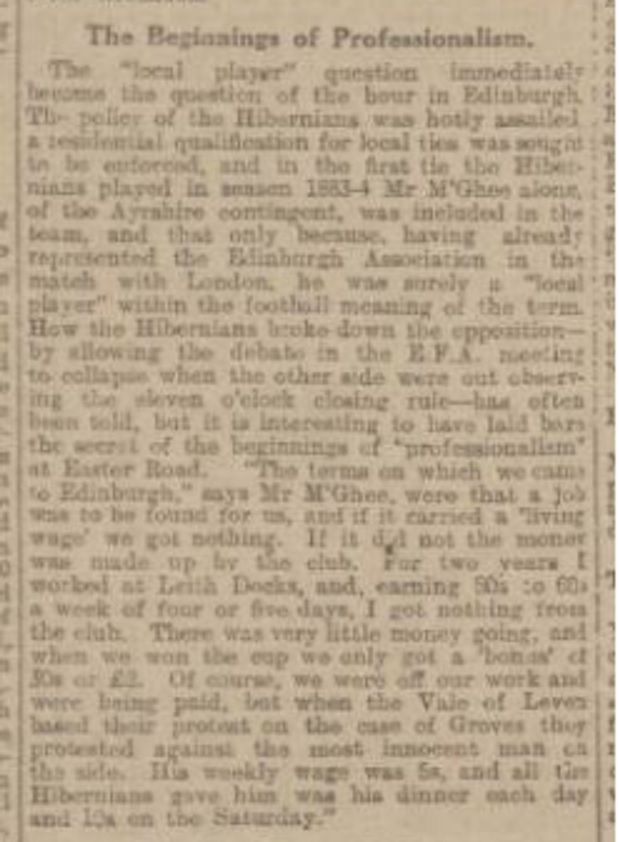

9) In Scotland, whilst much of the game was and remained local, the initial driver of professional football was from 1880 Queen's Park active use of what we would today call tapping-up to recruit non-local talent.

10) By 1886 England's aggressive response to increasing professionalism had collapsed, leaving Scotland completely exposed yet through Queen's Park pressure failing to react with consequences for what had been by far and away the most successful national team in Britain.

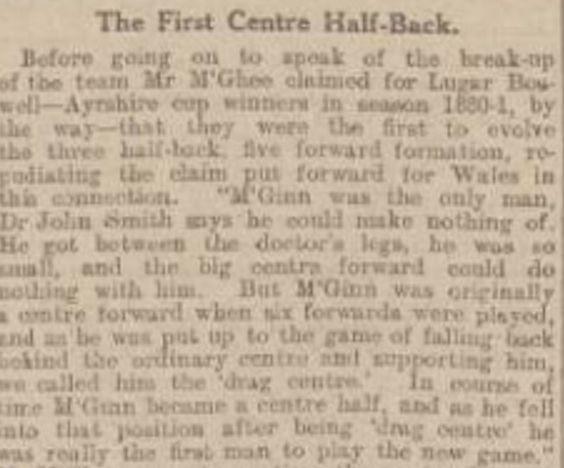

11) Again in the Vale of Leven the fundamentals of the Scottish-Game having been honed were in 1888 then augmented at Renton by the introduction of Scottish centre-half, The Pivot, essentially a fully functional mid-field, and its rapid transfer via personnel, "Scotch Professors", to wider Scotland, notably the newly created Celtic, and into England.

12) By 1898 the process of tactical transfer was largely complete, but, as the national team also recovered it position as professionalism in Scotland was finally accepted, the clubs there drawing just on local talent had been completely eliminated from the top-flight game but just the principles developed by them were now being carried internationally by players and/or coaches.

Foreword

This piece, this treatise is an attempt to look at, to be momentarily highfalutin, in an Aristotelian argumentative way and write the early history of first what will here at times be called "round-ball football", to distinguish it from the "oval" one, and then Association football and distinctive Scottish Association football not on the basis of the solely analogue input previously available but taking advantage of the data that has been digitalised over the last decade. It had also been begun with the potential for Hegelian synthesis but the conclusions seem finally to provide very little scope. The previous, as the academics like to call it, historiography has simply been wrong, indeed the continuation of an exercise in South British gas-lighting.

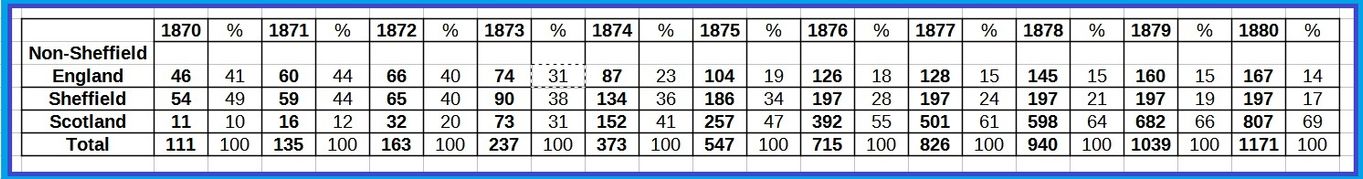

And the impulse for the work has been in terms of our Scottish football that the wealth of new information and the ability more easily to join its parts together has created a new, different, much revisable and revised picture, a novel historiography, of, just for the moment, mainly the thirty years from roughly 1870 to 1900 when Scots thinking on the game and the "Scottish-Game" were pre-eminent in Britain and therefore globally. With, if still interested, the main planks of the new un-gas-lit argument in chronological order being:

- Organised, inter-club, large-scale and therefore recognisably modern round-ball football was first developed from 1860 to local rules in Sheffield, England.

- Organised, non-mob football had existed in Scotland for several hundred years prior to point 1) but was regional, even local.

- As, from the mid-19th Century, modern Glasgow developed round-ball football came to Glasgow Green at the same time as Sheffield but was semi-organised.

- In 1862 the English John Thring published his pamphlet "The Rules of Foot-ball: The Winter Game. Revised for the use of schools" including his own rules for "The Simplest Game". Note the word "winter.

- London's Association football was founded in 1863 and throughout the late 1860s crucially nurtured by Sheffield to the point of "adulthood" and full independence from the oval-ball.

- In 1865 the first inter-city game, the pre-cursor to the International, was played between Nottingham and Sheffield, 18-a-side, to "Nottingham Rules".

- In the 1867 the Youdan Cup, the pre-cursor to the FA Cup, was played in Sheffield.

- By mid-1871 Glasgow's Queen's Park accepted the London FA Rules and Association football as a winter not, as previously had been the came at that club, a summer game.

- In February 1872 there was the first record of team formation in a major game. It came in the fifth "unofficial" international. Both "England" and "Scotland" played 11-a-side and 1-1-8.

- In early 1872 the notion of fully Association football and first Scottish thinking on it arrived through Queen's Park to Glasgow.

- In the 1872 FA Cup Final The Wanderers play 1-1-8 but The Royal Engineers 2-1-7

- In August 1872 Queen's Park in playing Airdrie using a 2-2-6 formation.

- In October 1872 Queen's Park in playing Granville revert to 1-2-7

- But in November 1872 in the first official international England form up as 1-2-7 but Queen's Park aka Scotland as 2-2-6 once more.

- In Scotland by early 1873 the impulse to and control of round-ball football, the Association game now dominant, moved from Glasgow Green to Queen's Park in the Southern Suburbs,

- In the second half of the 1872-73 season in Scotland Queen's Park revert to the 1-2-7 and 2-1-7 formations.

- In England in the second international in early 1873 Scotland retained 2-2-6 and England played 1-1-2-6

- In the FA Cup Final in 1873 both teams play 1-1-8.

- By 1873 also the original middle-class, first generation founders of Sheffield football were fully replaced by a second.

- By again 1873 in England Association football outwith London took root first in Birmingham at Calthorpe and then in North-East Lancashire.

- At the start of the 1873-4 season both Vale of Leven and Queen's Park are playing 2-2-6 and by November Renton is known to have taken that a stage further to 2-2-3-3, a shinty formation.

- By late 1873 the now tactical innovations reported by outside observers of position and passing, both short and long, in deliberate combination that would make for the first and distinctive iteration of the Scottish-Game would come from outwith a) Glasgow from Dunbartonshire's Vale of Leven and b) football from shinty.

- In the 1874 international Scotland still played 2-2-6 but England now tried 3-7.

- In the 1874 FA Cup Final both teams use 1-2-7, in the Scottish Cup Final both employ 2--2-6, which is possibly actually 2-2-2--4 or 2-2-3-3.

- In 1874 the original middle-class founders of the English FA fully replaced by alumni of the Public-School system.

- The World's first professional, round-ball footballer (SRP) was probably Sheffield and Sheffield Rules' Jack Hunter, followed in 1876 by "hybrid professionals" (HRP) from Scotland to Sheffield, J.J. Lang and Peter Andrews, then in 1878 by also Scottish, fully Association football players (URP), Archie Hunter to Aston Villa and Jimmy Love and Fergus Suter to Darwen.

- In the 1875 FA Cup Final the Old Etonians play 3-7 and The Royal Engineers now 2-1-7.

- In 1875 Renton became the first working-class team to reach the final of the Scottish Cup and therefore of a major, Association football competition. In it both teams line-up as 2-2-6, Renton quite possibly 2-2-3-3.

- In the 1875 international England play 3-7 and Scotland 2-2-5-1, possibly 2-2-3-2-1.

- In three weeks in March 1876 in the Scotland-England international the former take the field as 2-2-6 once more and England as 2-2-4-2, adopting for the first time the Scottish defensive formation, in the Scottish Cup Final both teams are 2-2-6 and in the FA Cup Final The Wanderers 2-2-6 but still Old Etonians 1-2-7.

- In 1876 Queen's Park are known to be also playing 2-2-3-3

- In its first international (against Scotland) Wales used 2-2-6, as did the Scots

- By 1877 the centre of the on-field game in Scotland, the Scottish-game, had fully moved from Glasgow to the Vale of Leven, the working-class Vale of Leven club winning the Scottish Cup, it and would effectively remain there for the next fifteen years as the centre of control of the game North of the Border remained in Glasgow

- The 1877 Scottish Cup Final had both teams playing 2-2-6, the FA Cup Final finally both also 2-2-6 but in the international England tried 3-1-6, even 3-1-3-3 and Scotland seemingly 1-3-4-2, perhaps 1-3-2-4, so with a sweeper behind three half-backs, in McDougall and Smith two big centre-forwards and Ferguson seemingly solo on the left-wing.

- The Sheffield Rules game was in 1877 absorbed by London, creating the "Unified Rules", but leading, because of dissent from within Sheffield itself, to the partial collapse of the game there for the next decade.

- In the 1878 Scotland-England international both teams play 2-2-6, in the FA Cup Final it was the same as, of course, it was with the Scottish Cup Final.

- In 1878-9 in North Wales by Wrexham 2-3-5 , The Pyramid, began to be used regularly.

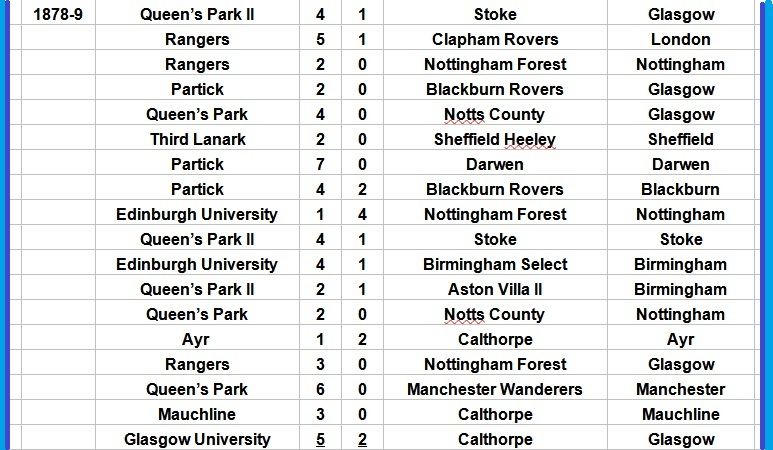

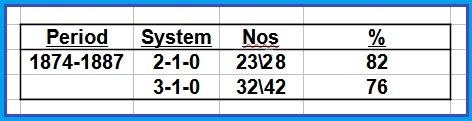

- In all three of the major games at the end of the 1878-9 season all teams use 2-2-6.

- In 1879 the first Renton club collapsed just as Vale of Leven, The Vale, won the Scottish Cup for the third year in a row

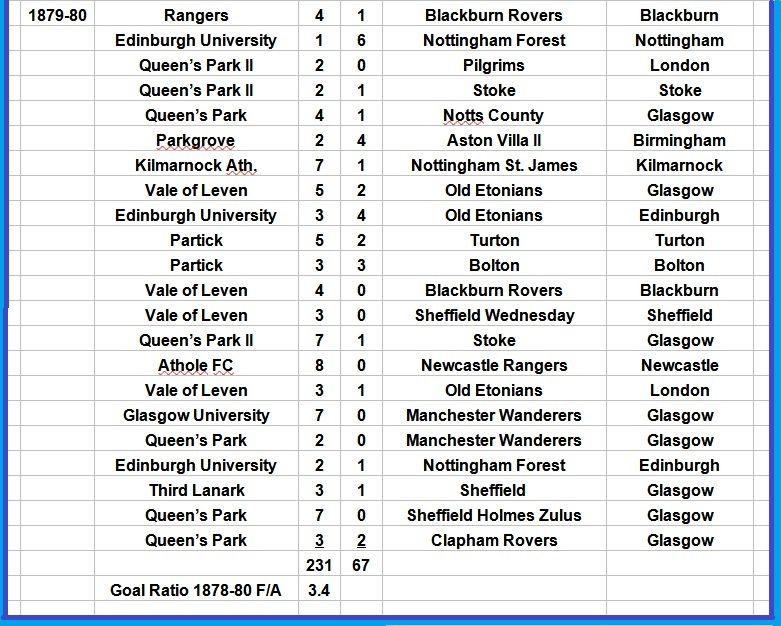

- In the two Cup games at the end of the 1879-80 season all teams use 2-2-6 but in the Wales-England international both elevens are recorded as lining up not just as 2-2-3-3, the two centre-forwards playing one behind the other but the wing-pairings with the front one tucked in-field in two up-turned Vs. The inside-forward but not yet The Pyramid is seen to be born.

- Queen's Park responded to The Vale by from 1880 initiating the recruitment of better players from outwith the club through a policy of "assembling" from i.e. "tapping-up" other teams mainly in the Glasgow area but thereby actually forcing the setting in train of the process to eventual professionalism in Scotland and almost its own demise.

- In 1882 Ireland plays its first international and using 2-2-6.

- In 1882 Wales use both 2-3-5 and perhaps The Pyramid in beating England for the first time but will revert the following season.

- In 1882 Scotland inflicted the third heavy, international defeat in a row of England.

- In 1882 Lane Jackson in London started the anti-Scottish, anti-working-class Corinthian project.

- In 1882 in England the first northern and also working-class team reached the FA Cup Final but it was not from Sheffield, where working-class football had first been played but was Blackburn Rovers and with three Scots in its eleven.

- In 1882 in England initial measures were taken against non-local professionals i.e. Scots and completely ignored

- The Renton club re-formed in 1882

- In 1883 Blackburn Olympic became the first northern and working-class team to win the FA Cup

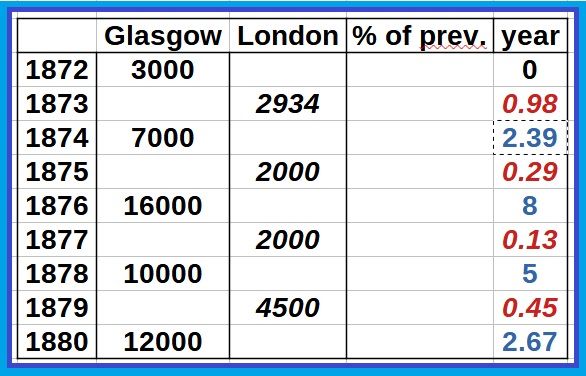

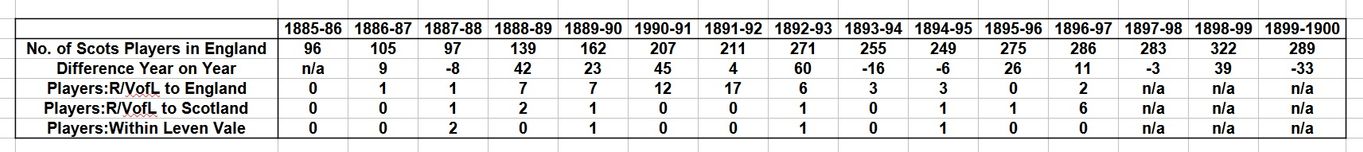

- From five in 1878-9 the number of Scots playing as effectively professionals In England had risen to about fifteen in 1881-2 and nearly forty in 1883-4

- In January 1884 in England objections for professionalism were with the English Football Association raised against an "assembled" Preston North End by a London club. Preston was found guilty and disqualified from the FA Cup.

- "Assembled" Queen's Park do not agree to a postponement of the 1884 Scottish Cup Final against a Vale of Leven, "local" First Team decimated by illness. Vale of Leven withdraw

- In the 1884 Scotland-England international England line up as 2-3-5 with Indian-born, Gaelic-speaking Scotsman, Stuart McCrae, as centre-half.

- In 1885 new anti-professionalism measures formulated by Lane Jackson introduced in England by London, objected to by Northern English clubs, which threatened schism, with London more or less backing down, the exception being annual registration, with what otherwise remained of the policy in any case again ignored.

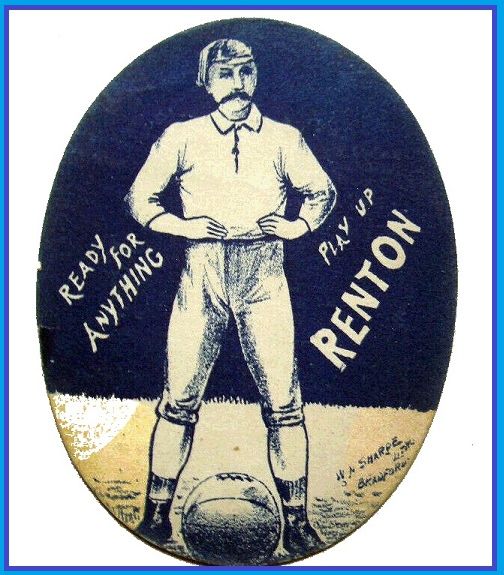

- In 1885 local Renton reach and win the Scottish Cup Final beating neighbouring and also local Vale of Leven

- In the 1885 FA Cup Final 2-3-5 is used for the first time and by Blackburn Rovers with at centre-half the Scot, Hugh Mcintyre, whilst England against Scotland use the same formation with Blackburn's outer half-back and Mcintyre-protege, James Forrest, in the McIntyre role.

- In 1886 Blackburn Rovers win the FA Cup for the third time in a row, now with four Scots in its otherwise local eleven and a first recognised Secretary cum Manager, the Scot, Thomas Mitchell. He employs 2-3-5 as do opponents, West Bromwich.

- In 1886 England with nine Corinthian players, the maximum to be selected, was held, 1-1, by, from the 65th minute, a 10-man Scotland, Queen's Park's George Somerville scoring the equaliser in the 80th minute and with Lane Jackson an umpire

- In the Scottish Cup Final both teams still use 2-2-6

- In 1886 all international teams except Scotland use 2-3-5

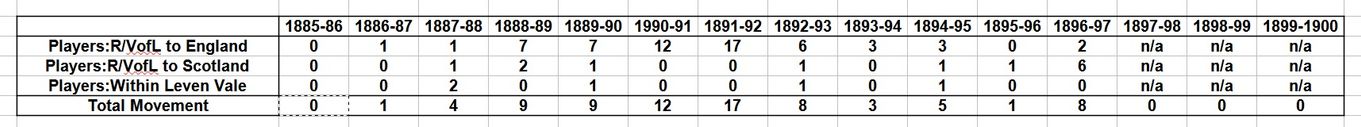

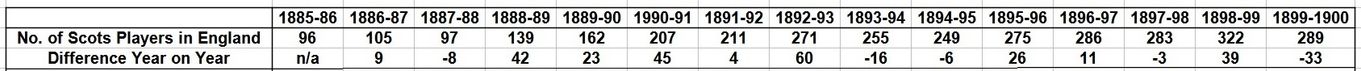

- In 1886-7 the number of Scottish professionals in England passes the hundred mark

- In 1887 the Scottish FA at the behest essentially of Queen's Park bans all Scottish club participation in the FA Cup because of professional, English clubs taking part. Seven had taken part the previous season.

- In 1887 local Dumbarton reach but lose the Scottish Cup Final to at least partially assembled Hibernian but with both teams now also using standard 2-3-5, i.e. with one of the centre-forwards dropping back.

- In 1888 John Goodall raised and learning his football in Kilmarnock but born in London, because his soldier father was serving there at the time, first selected for England.

- In 1888 President of the English FA awards his match ball to winners of the FA Cup, West Bromwich, on the grounds that its team is all English (Defeated Preston North End having six Scots plus John Goodall in its team).

- In 1888 local Renton, playing its new 2-2-1-2-3 formation with what would become known at the Scottish Centre-Half or Pivot, differently an inside forward dropping back, win the Scottish Cup, against 2-3-5 Cambuslang, and then defeat both West Bromwich and Preston North End to become de jure "World Champions".

- In 1888 Scotland lose to England for the first time in almost a decade, at home and badly, 0-5, 0-4 down by half-time, with some kind of very unsuccessful mish-mash of 2-2-1-2-3 on 2-3-5 and serious problems on the right side of the defence.

- In 1888 Celtic is formed entirely by tapping-up, taking two Renton players, including James Kelly to be part of its first eleven.

- In 1889 Preston North End win the English Cup and League Double with again six Scots players in its first team plus John Goodall.

- In 1889 Scotland beat England by playing effectively a 2-2.5-0.5-5.

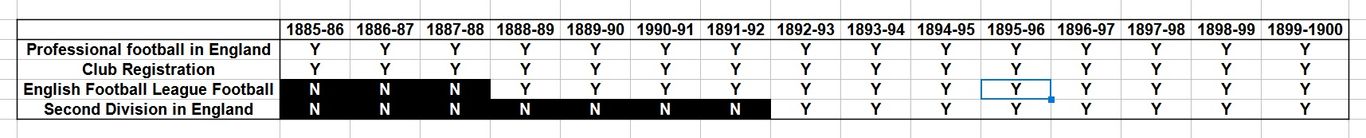

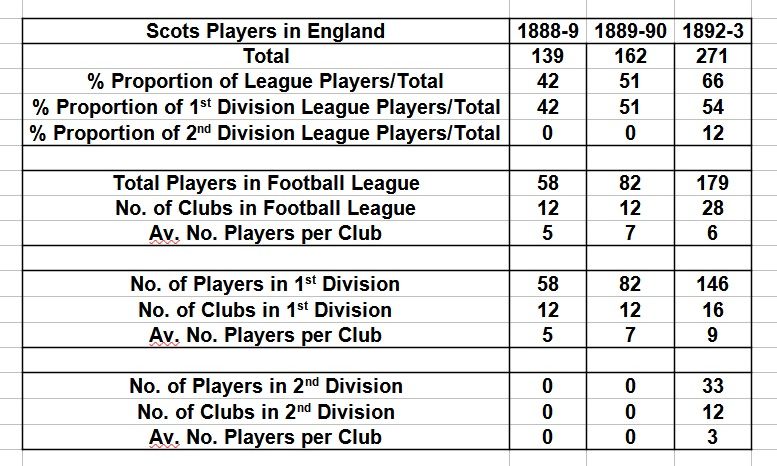

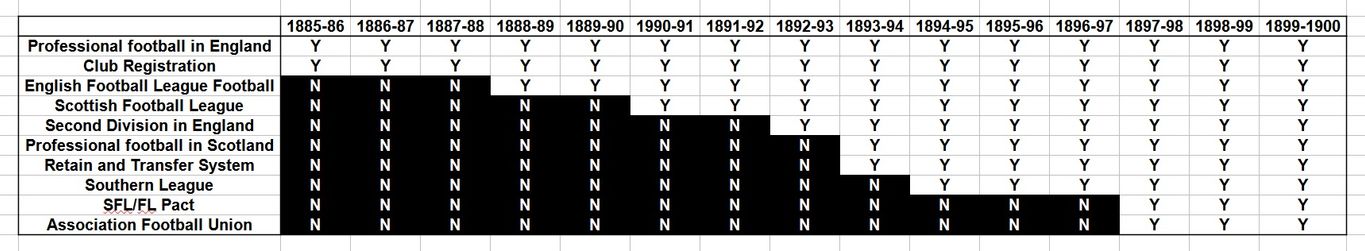

- Numbers moving South to play professionally in England, the total going from a total of just less than 100 for 1887-8 to over 200 by 1891-92, or seven per top-flight team, the Scottish national team therefore being severely weakened.

- In 1890 the Scottish League kicks off. Queen's Park, assembled Cup-winner over local Vale of Leven, is invited to join but does not take up the offer.

- Renton is expelled from the Scottish Cup for alleged involvement with professionalism and takes the SFA to court.

- At the end of its first season local Dumbarton is with an assembled Rangers the Scottish League Champion, Renton wins court case and is reinstated, Vale of Leven reaches the Cup semi-final and partially-assembled Queen's Park takes the trophy.

- For the 1891-92 the number of Scottish professionals in England passes the two hundred and fifty mark.

- At the end of the 1891-2 season local Dumbarton is again League Champion but local Vale of Leven is not re-elected.

- In 1893 assembled Celtic win the League for the first time, again partially-assembled Queen's Park win the Cup for the last time.

- In 1893 professionalism is legitimised in Scottish football and the Second Division is formed.

- In 1894 local Renton is relegated to the Second Division.

- In 1895 local Renton from the Second Division reach but lose the Scottish Cup Final.

- In 1896 residence requirement for Scottish international is removed. Scotland beat England for the first time in six seasons. James Cowan of Villa ex. Renton as Pivot. John Goodall is in the England side for the last time.

- In 1896 local Dumbarton is relegated to the Second Division.

- In 1897 local Dumbarton reach the Scottish Cup Final but resign from the Scottish League.

- In 1898 local Renton resign from the Scottish League as for the following season the number of Scottish professionals in England reaches its recorded maximum of 300 plus.

- In 1899 fully-assembled Rangers beat almost fully-assembled Celtic in the Scottish Cup Final.

- In 1900 Queen's Park join the Scottish League for the first time and into its First Division. Scotland beats England 4-1, Bob McColl scores a hat-trick. Alex Raisbeck is Pivot. Assembled Celtic beat a now mainly local Queen's Park in the Scottish Cup Final, Queens' Park no longer able to compete in the transfer market?

Introduction

In 2023 it was suggested that the new thinking on early Scottish, foot-ball and football history to the beginning of the Second World War, and, indeed, football history in that same period more generally, emanating from the SFHG and others might be worthy of a academic recognition through a PhD. And one over two to three years at Edinburgh University was applied for, but on the understanding 1) that it would be in the name of the whole group and not one person and 2) it would be a replacement for or at the very least the dominant part of a merging with the old thinking i.e. an antithesis to the current thesis leading at the least to synthesis, if not more.

The proposal was, however, without real explanation at the time but possibility hinterland, knocked back, which denied the academic route but saved £15,000 and, due to on-line technology, still left fully open the possibility of it being worked through, completed and simply posted. And what follows here is the result, not in a heavy but largely ignorable and ignored tome but in a series of articles, essays, if you like, sometimes loosely-linked, that state and allow, with more knowledge still becoming available, the amendment the current thesis yet without much need for compromise. The crux, in something of a repetition, of the offering on the one hand is that:

- Association, Association Rules (AR) football is provably not a product of the English Public School system.

- At its creation it probably would not have survived but for the Sheffield Rules (SR) game and the input specifically of Sheffield F.C..

- Much of the off- and on-field innovation in the early game also came from that same Yorkshire city before, for internal reasons, its football imploded.

- From the early 1870s when the game arrived North of the Border it was Scotland and Scots, our country and countrymen, and not England and the English, which and who for much of the next fifty years picked up the baton and successfully ran with it.

- But that it was within Scotland but a) not at Glasgow's Queen's Park club as formally posited, b) major tactical innovation took place at two stages over the fifteen years from baton transfer fundamentally to change the framework of our game on-field, c) Association football was in the same period consolidated in first Scotland and then wider Britain on-field and but also in-club as a universal and not a class-riven sport, d) it caused, both unofficially and officially, the professionalisation of the game and in doing so created the competitive league structures followed by most sports and by most of the World and d) Scotland was then the driving force in taking that same game global.

But it begins with a little background and immediate thanks to Ged O'Brien, the founding Curator of the Scottish Football Museum, Europe's first, and to Andy Mitchell, the doyen of real historians of football in Scotland and wider Scottish sport. Thanks to O'Brien there has been the identification from 1627 at Anwoth in Dumfries & Galloway of what is just now considered to be the oldest football field in Scotland, Britain and therefore worldwide. But here a note: We have no indication of whether it was used in summer or winter or both, although knowing the Dumfriesshire winter the former must be favourite. And from Mitchell we have his research into John Hope and the Foot-Ball club he founded in Edinburgh in 1824 and ran for the best part of twenty years. Gone into in depth in John Hutchinson and Andy's book, "1824 The World's First Football Club" we have a strong, and perhaps the earliest example of what could be called football's, that is the round-ball but not yet Association game's "modern" era of both written codification plus games, albeit then only intra-club, and continued organisation over an extended period of seventeen years.

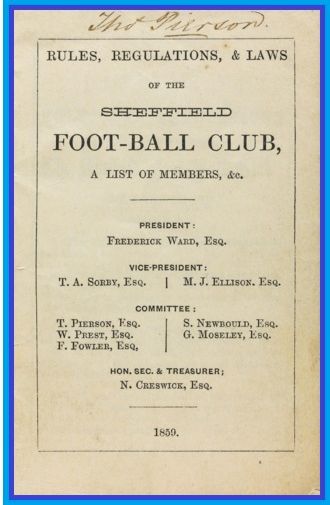

And this trend was further covered to the late 1850s in this, in retrospect, admittedly somewhat peevish, SSHG piece, "The Absurdity of the Parochial" (See next column). It was written in response to the claim by Sheffield, Home of Football (Our Brackets: Not Association football) that it was in 1857 and at Sheffield FC, the important nullifying proviso being that its rules were at that stage also only in-house. You will note here that the English Public Schools have not been mentioned because codification of their footballing iterations came mostly later, Rugby School in 1845 with its thirty-seven being the exception and with our SFHG Supplementary Timeline giving the more or less definitive chronology.

However, when it comes to organised, competitive, inter-club football, but still not the Association game, then it is the game played on Boxing Day 1860 again in Sheffield between Sheffield and Hallam F.C.s that is the marker. Indeed it is those two clubs and almost twenty more that followed in the same city over the next three years, which at that time represented the round-ball game's only real driver.

And the truth is that even with, in London, the formation in 1863 of the Football Association and therefore of embryonic "soccer" that role as driver did not really alter. It is questionable whether the FA would have survived birth had it not been for the support, even including travelling down to meetings, by a remarkably benign, philanthropic, almost paternal Sheffield and in 1866, even whether it, the London FA, might have dissolved itself but for the same. And through these three early years it was also Sheffield, which was the source, on-field, of a good number of sensible, practical rule-amendments as well as, off-field, competitive and even marketing innovation. It agreed to play, indeed suggested, inter-city, i.e. regional matches, conceptually the forerunner of the international, even agreeing that they take place to local rules. And it in the Youdan Cup produced the blueprint for the FA Cup.

But the question remains 'why', to which the answer might lie in origin and personality. Sheffield Rules football was very much the child of the city's legal profession. What it was not was founded by Public School boys. There was influence, particularly, it seems in the rules, from young men returning from school further south, noticeably Harrow, but the two men who were founders of Sheffield F.C. and therefore considered to be founders of Sheffield-Game, Nathaniel Crestwick and William Prest, were a locally-educated solicitor and a wine-merchant respectively and neither in footballing terms young. The former was twenty-five in 1857, the latter twenty-four. They were comfortably middle- but not upper-class and had come to the game sedately through cricket. And even when they stepped back, Crestwick in 1862, their successors were until 1866 William Chesterman, stepping down aged twenty-nine and a maker of measuring-instruments, and from 1866 to 1876 Harry Chambers, another lawyer, who at twenty-five/twenty-six also served for its first two years as President of the Sheffield Football Association when it was formed in 1867.

And this was a pattern that was fairly closely matched six years later in London. Of the four main, initial office bearers one was a solicitor, two were stockbrokers, and one a wine-importer. Moreover, only one, Robert Graham, had been to a public school, Cheltenham, but for just a year, three of them had come to the sport this time from rowing and Ebenezer Morley, regarded as The Father of the Football Association and therefore of Association football, had been born the same year as Crestwick, so in 1863 was already thirty-five, was also a solicitor, non-Public School and a Yorkshire-man to boot. He had been born and lived until twenty-two in Hull, and as the son and grandson of non-Conformist ministers so no more than middle middle-class.

It meant that one hundred and seventy miles apart there were two groups of football enthusiasts, who could talk to and interact with each other, not just on a sporting level but culturally and professionally. And talk and interact they certainly did. Sheffield's Chambers in his records states that he attended the first London meetings of the (English) Football Association in 1863, thus giving Northern encouragement as it struggled into life. In January 1864 he was played in the match in London to test the FA's new laws. He also took part in 1866 in the first inter-city match. It was played in Battersea Park between London and Sheffield teams and to London Rules. As to Chesterman he had been the one to propose the London versus Sheffield game, was Sheffield captain that day, represented Sheffield F.C. at the 1867 meeting of the FA, arguing against, giving it Northern backbone, as it almost dissolved itself, and that same day was elected to the FA, the London FA Committee and served on it until 1871. And in doing so he must have reported on developments in the Sheffield game, passing on its thoughts on adjustment of rules and competition, indeed competitions. The Youdan Cup of 1867 was followed a year later by the Cromwell Cup.

Thus by 1867 the characters, who were to dominate English football's off-field, some for just the next few years, two for extended periods, might have been beginning to fall into place but were not in charge. John Alcock had been an FA Committee member from its inception until replaced in 1866 by his 24-year-old and briefly Harrovian younger brother, Charles Alcock. Harry Chambers was his contemporary, when he arrived the next year. Then in 1868, the year the Association actually ran out of money with the officers covering the shortfall out of their own pockets, Arthur Kinnaird, just twenty-one at the time, would join and he would be followed in 1869 to 1872 by James Kirkpatrick, The Quiet Baron, just a year older than both Chambers and Alcock. He was the man who would go on to organise with Kinnaird the "Scottish" input into the series of five unofficial internationals from 1870, captaining the mainly Diasporan side for the first two matches. He also provides a link back to very first day's of the modern Scottish game in that his father had in Edinburgh been a member of John Hope's Foot-Ball Club. And in the background there was first Robert and then James Smith, who had both come South for work but were the liaison-men with their former club, Queen's Park in Glasgow. Robert Smith would play in the second, third and fourth of Kirkpatrick's and then Kinnaird's international sides as well as for South Norwood and in the first two official internationals before emigrating to America later in 1873. James, who would play in the first official international, would remain, still the link, in London until his death back in Scotland in 1876.

So given that Morley was still in overall control and Graham would remain Secretary and Treasurer until February 1870, only then to be replaced by the younger Alcock, there was in place from the turn of the decade an FA Committee, with Graham still on it until 1871, that was finally settled in terms of core personnel and influences. Moreover, from perhaps 10 member clubs in 1866, the number had grown to fifty or so, with Sheffield about the same, the organisation as a whole was finally also financially stable and could therefore move on. The internationals, the first in March 1870 with organisation clearly already commenced pre-Alcock, were one aspect. The Youdan-like FA Cup was another. A third was the agreement from Queen's Park to enter the FA Cup by its start in November 1871 but presumably negotiated earlier in the year. And finally there was the first official international in 1872, quite possibly seen as necessary following the example, and challenge, of the first-ever rugby one of March 1871, firstly, taking place in Scotland in Edinburgh, secondly, with actual Scottish Scots in the team and, thirdly, won by Scotland. At that point it might have looked to Queen's Park as if round-ball football North of the Border was in danger of being chased South completely, about which it believed, to its eternal credit, something could and would be done. However, all the above throws some doubt upon the real role of Charles Alcock. To some he was football's first marketing genius, but perhaps not.

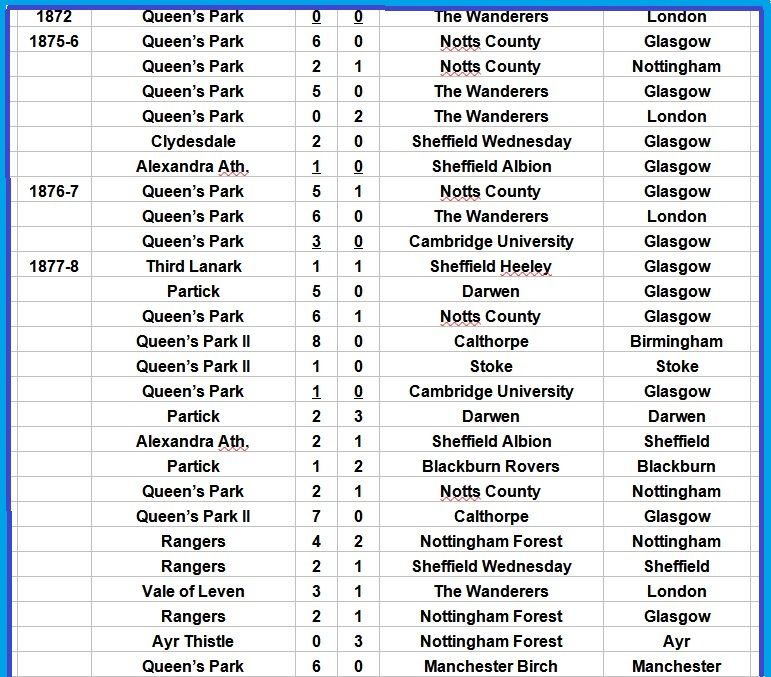

As it turned out Scotland's first participation in serious footballing competition, Queen's Park's entry into the FA Cup, could not have gone better. Twice the club was drawn at home to a school team from Lincolnshire, quite possibly even today one of the most difficult places in Britain from where to get to Glasgow, never mind the cost. Once the London FA was able to defer the problem with byes to the next round. On the second occasion there was no helping Donington. It had to scratch leaving the Glasgow a free run without touching a ball to the semi-final. If the draw had been, Heaven forbid, tampered with, it would turn out to be masterly, again quite possibly changing the course not just of Association football but football more generically forever. If not, and it was just happy serendipity, then fate was smiling broadly when the hardly-known, Scottish club travelled to the London Oval for the game against the assumed winners, The Wanderers, Alcock's team, and shut them out.

In fact the result was itself perhaps nothing special or at least not too unexpected. The London team was perhaps the best the South had to offer but hardly a whirlwind. It had also had a walk-over and a bye to get to the round of four and had scored three goal to one in the two matches it had had to play, one being another 0-0 draw. However, with the game at The Kennington Oval, the fact that Queen's Park could not afford to travel South again for the replay and The Wanderers went on win the trophy, defeating The Royal Engineers in the final, did generate interest North of the Border. Indeed enough that other clubs playing other footballs, cricket and other sports, notably shinty, were now more prepared to listen more attentively to what Queen's Park had to say. And Queen's Park were also forward-thinking in this period and beyond, prepared to travel to demonstrate the sport, for which they were the first and only Scottish advocate or at least seemed so.

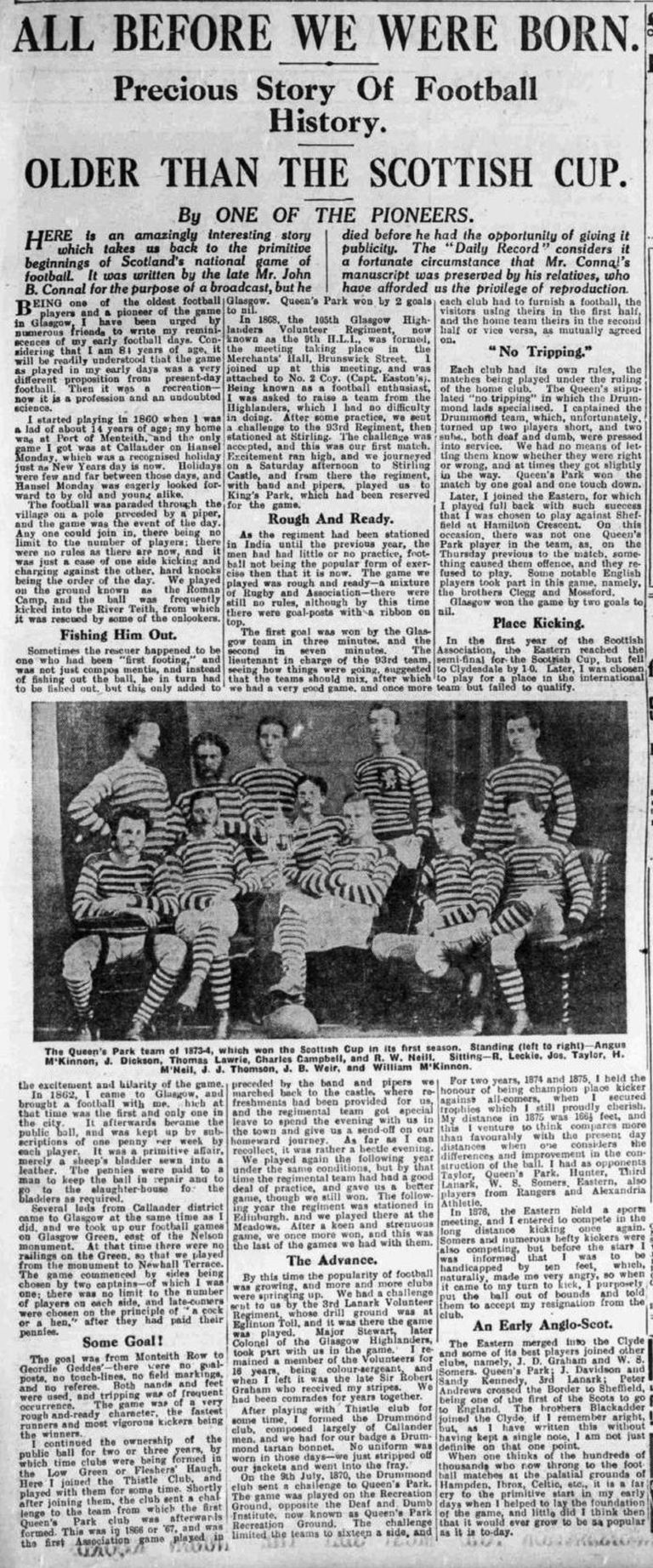

In fact it now seems that, thanks in large part to research from Andy Mitchell once more and Richard McBrearty, curator of the Scottish Football Museum, with his blog The Origins of Scottish Football, round-ball football, 11-a-side or otherwise, and even to Association Rules had been already played in Glasgow and along the Solway coast, specifically in and around Stranraer and also by Annan. In the first case it had and would centre around John Connell, who in 1861/2 in his mid-teens had arrived from Perthshire to the old town above Glasgow Green and with a ball that he would hire out for games; what he called a "public ball". His full story as initially non-Association and later Association footballer, a player for Glasgow against Sheffield and almost an international (he was a reserve against England in 1875) is probably best told in Andy Mitchell's piece, The Man who owned the first football in Glasgow, in this SFHG biography and in his own words in an article, which can accessed in readable form and with greater detail by clicking on its image in the next column. The gist of it is that, once in the city, from where he stayed Connell could drop down High St. to Low Green or Fleshers' Haugh, where ad-hoc games, using both feet and hands but surely with basic rules understood from week to week, seem to have been taking place from at least 1862.

It means therefore that the first centre of Glasgow football was actually north of the Clyde in the city itself not, as wrongly advocated elsewhere, south of the river in the newly developing then still Renfrewshire suburbs. Furthermore, it would also be from Glasgow Green that by 1866 or 1867 the first attempts at teams cum clubs would emerge. The Orkney Exiles was one such earliest on. Connell himself mentions that at about that time he joined the Thistle club. And it was that same Thistle, which, on the formation of Queens Park, the Southern Suburbs' initial specifically but note summer/autumn-only football entity, was, and not the other way round, first to issue a challenge; one accepted on 1st August 1868. Indeed it came from Connell himself, (See: Queen's Park History 1868-1870), indicating that it was he, who had the finger very much on the local footballing pulse. It might even be no exaggeration that in fact he was that pulse and for the best part of a decade. It was again he, when Queen's Park was still getting virtually no interest in its adopted version of neo-Association rules and at least equally emergent rugby was getting much of the attention, who again would challenge it on joining, indeed, in 1869/70 forming, his next but short-lived club, Drummond. The challenge would be met in July 1870. The club was made up of fellow lads from Perthshire, playing, it seems, to non-Association, still hybrid rules but with the change and adaption about to come.

Meanwhile, however, it now seems that Association Rules, if not quite in their entirety, had been seen on Scottish soil, if only just. John Sholto Douglas, the 9th Marquis of Queensbury, born in in 1844 in Florence in Italy, compiler of boxing's Queensbury Rules, elder brother of Lady Florence Dixie, who in 1895 would become the first patron of the first women's football club, the London-based British Ladies' F.C., had, aged fourteen, inherited the title on the death of his father in 1858. He would then be educated in the Navy, serving until 1864, aged twenty, and before going up to Oxford for two years, not completing a degree, marrying in 1866 and probably for a while subsequently living in London. And it must have been there he, a consummate sportsman, came into contact with football. Even in terms of his known involvement in cricket he would have moved in the same circles as his almost contemporary, Scottish, footballing nobles, Lord Arthur Kinnaird and James Kirkpatrick.

So it seems that when he moved north in 1867/8 for a couple of years at least - his elder child was born in 1868 at Kinmount House, the family seat at Cummertrees by Annan, his second in 1870 in Worcestershire - he took the essence of the London game with him, perhaps combining it with a local tradition of other football and setting up a small series of equally local matches to Association Rules but with larger teams, 15- a-side being mentioned, and he himself playing. But note, these were not "Yuletide Games". They were played not in mid-winter but from the middle of March 1868 so as Spring first arrived on the Solway, which may have been just chance but could equally have been a reflection, outwith alcohol-fuelled Hogmanay, again of an older, specifically summer, round-ball sport. Indeed, with, for example, the Anwoth ground it is hard to imagine anyone even then in far hardier times looking forward to a kick-about up there on the top of a hill in the freezing horizontal rain, sleet and snow of anytime between November and March/April.

It is these games and the pioneering work on early South Scottish football by Richard McBrearty, the Curator of the Scottish Football Museum and PhD Researcher at Stirling University, and covered in his blog Scottish Football Origins that were gone into more detail in the article reshown here in the adjacent column and entitled "Stranraer - and the Coming of Football to Scotland. And it is it, which also takes us onto Stranraer and Newton Stewart and the third specifically Scots arrival of the early, not yet modern but modernish game.

The rise of wide-scale competitive sport was and continued for a good century to be made possible by the railways. It had arrived at Stranraer in 1862, connecting it with Castle Douglas via Newton Stewart. Castle Douglas had itself been connected to Dumfries in 1859 and Dumfries to to the Glasgow to Carlisle line in 1850. As to organised football, it arrived in Stranraer at least by 1865 by when there were four teams, three of which are still identifiable as areas of the town. Of the how and why it got there there is is no current idea. It could have come from north or south. It may even have been once more a long-standing tradition, again a summer one. The quote from John Boyd's 2002 paper "The First Thirty Years" is "they played intermittently on Wednesday afternoons and during the summer evenings on farm fields". However, clearly cooperation between the teams existed, suggesting even a local competition, because that same year, 1865, a Stranraer team, a "town" team, travelled the twenty-five miles to Newton Stewart. It was to take part in the first, over the next ten years, of three known, 11-a-side encounters, presumably again to agreed rules other than just number of players against specifically Cree Rovers, a team that according to other sources would not exist for another decade and more.

Furthermore we have the names of the Stranraer players taking part and there is (See again the article) remarkable continuity of players from 1865 to 1870, even some to 1875 and the move in the interim from non-Association to fully Association Rules. Moreover, those names, thanks to the historically game-changing Scotland's People web-site, can to a degree be pinpointed to the town itself, to surrounding villages and possibly to Ayr. Despite Ayr F.C., one of the two component clubs of present-day Ayr United, having its foundation as 1879, we know, again from Queen's Park's History, that the Cathcart/Crosshill club in 1868 put out feelers for a game to "newly-formed Ayr Football Club" suggesting, similar to Glasgow Green, a form of ad-hoc football already being played in that town before that "official" date, perhaps even before 1865. Here more work is needed. - a deeper trawl through the local papers, perhaps.

However, let us at this point turn attention back to said Glasgow, initially to Queen's Park F.C. but then not the round- but the oval ball-game. The foundation story of Queen's Park is well-known. It is one of a form of presumably round-ball but ad-hoc football being in 1867 played on Queen's Park itself by local YMCA members and seen by a group of more northerly Scots, from Perthshire, Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire and Moray, forced from their former place of practice of field-athletics by Lorne Terrace in Strathbungo by encroaching development. The latter joined in with the former, took to what they saw and decided to and did form a football-club, but one with a difference, indeed, that was in a sense elitist. This is all excellently covered in the chapter "The Beginning" of the modern Queen's Park's History and by Robinson's 1920 "

History of the Queen's Park Football Club 1867 - 1917

Renton & The Vale - The Making, Remaking, Unmaking, Breaking and the Who. (But the creation of the Scottish Game)".

"Episode 1: The Making

So this story begins not in mid- or late but early 1872. In March Queen's Park, having from November 1871 received byes to the semi-final of the first London FA Challenge Cup, the FA Cup, travelled to London to face The Wanderers. The result was a draw and, with the visitors unable to finance travel to the replay, they had to default and the home team went on to take the trophy.

Yet the one meeting that did take place tells us several things. The first is that, in order to take part Queen's Park had agreed a twofold acceptance; that Association football was a winter game and the London rules rather than its own would from now on apply. The second is two facts emerge, a) we know the Queen's Park team - Gardner, Edmiston, Hepburn, Ker, Leckie, J Smith, R. Smith, Taylor, Walker, Wotherspoon and Weir - and b) just now we do not know the formation. Moreover, we are also aware from contemporary sources that, whilst the internationals between England and Scotland, now designated as unofficial, all of which had taken place also in London, the first in March 1870 and last just a month earlier, had had not inconsiderable Press-attention, this club-match generated still more but also actually not much on-field activity. A month later a single match - also a nil-nil draw - was played by Queen's Park against Granville, newly officially-formed just up a few hundred yards up the road at Myrtle Park. But that was it.

In fact the game after that was not to be until 28th August and the one after that on 19th October; initially against Airdrie, an emphatic 6-0 win, and then Granville once more, again a win, 4-0,. But there was a difference. In both cases we have the teams - Gardner, Wotherspoon, Taylor, Thomson, McKenzie, Leckie, Weir, Ker, McKinnon, Rae and then Thomson, Taylor, Gardner, Hepburn, Leckie, Weir, Wotherspoon, Grant, Rhind, McKinnon and Rae respectively with captain, Robert Gardiner, in the first playing in goal and in the second as a half-back. But crucially we also have the formations. In the second match, just as The Vale is reported as in Alexandria holding its first practice, Queen's Park, according to The Glasgow Herald, seems to have played, as was the case with English teams of the era, 1-2-7 but in the former, again from The Herald, it had been a completely innovative 2-2-6, the same shape that was to be employed, in the penultimate encounter of the year, played now in Glasgow and the World's first official international.

Now at this point we have to wind back slightly. At some point still in 1872, said to have been in the Summer or Autumn but seemingly before December, Queen's Park, as part of its programme of demonstrating specifically the Association game and creating opponents had travelled to the valley of the Dunbartonshire Leven, to the Park Neuk recreation-ground specifically, on riverside itself in Alexandria. No-one knows exactly when it was but Vale of Leven Football Club is said to have been formed on 20th August, suggesting, albeit as a longish shot, it may have been then with the possibility that it could have been the inspiration, even the source of the formational experimentation just a fortnight later.

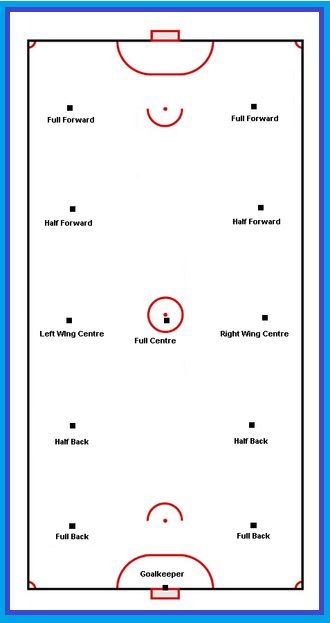

And the reason may well be Scotland's ancient game of shinty, now finally starting to achieve rightful recognition as an origin of ice-hockey and even golf. In the upper valley of the Leven, where the Orr Ewing brothers, Alexander and John, had in the 1830s founded their calico printing-works, employing often near-Highland labour, it had become the winter game. The first recorded shinty match between the two establishments had been in 1852. In 1870, so just two years before the visit of Queen's Park, 2,000 or so spectators are said to have come to the annual encounter. They and the young men on the field-of-play were thoroughly versed in the old game and its stands to reason that they would have approached the new one with it in mind. It is even said that when they were invited to take the field at Park Neuk to play against the Glasgow men first they did so in shinty formation.

That said, even today with shinty formations differing between the north and south Highlands, the former regarded, in the slightly tongue-in-cheek words of Hugh-Dan MacLennan, as "hell for leather wing play", two things stand out from the Southern one (shown above) as being not just potentially transferable but one hundred and fifty years ago actually transferred to the football field. The first is the block-four defence; what turns out to have been Queen's Park captain Gardner's perhaps novelty but one he might already have been aware of, picked up from the shinty he must have seen or even played in Glasgow, his home-town, or Paisley, that of his parents, but with the possibility it had on Park Neuk been noted for its effectiveness and adopted. The second is the vertical forward pairings.

Here the use of the words "perhaps novelty" should be explained. Reason one is it is well-documented that in the World's first official football international, played in Glasgow on 30th November 1872 between an England team and a Scottish one, captained by Robert Gardner and drawn mainly from Queen's Park, the English played 1-1-1-7 and we 2-2-6, i.e. the block-four. Reason two is because on the 21st December 1872 The Vale travelled to Glasgow to Queen's Park for the first of four encounters over the rest of the 1872-3 season. Again we know the team - William Ker, Joe Taylor, David Wotherspoon, James Thomson, Jimmy Weir, Bob Leckie, Alex Rhind, Willie Mackinnon, Andrew Spiers, William Keay, the referee of the first, official international, and Archie Rae, future SFA Secretary, but no Gardner - and that Queen's Park would win easily, 3-0, but just now have no formation. However, that would not be the case for the remaining three encounters and here is the crux. Queen's Park, even with Gardner back in the elevens as twice goalkeeper and then a forward and contrary to myth, twice played 1-2-7 once more and then 2-1-7, i.e. Queen's Park went back, indeed backwards, to the English way. Yet their up-country, newly-come opponents took the field on all three occasions as a 2-2-6, the apparently new Scottish way, either because they were either very good and fast learners (as incidentally Clydesdale must have been also) or because, it has to be said once more, it was what they already knew from old, were comfortable with and, having passed it on once for it just now to be seemingly rejected, ensured, whether deliberately or not, it was to be carried forward and ad infinitum. Even today it is the foundation, on which a back three, four or five plus matching mid-field is laid with the steps from then to now quite clearly discernible.

In fact Queen's Park, after the third Vale match, two draws and a Queen's Park win, was that season to play just one more fixture, a home win, 1-0, over Glasgow Wanderers from this time just down the road in Cathcart. Moreover, it seems also to have been the last one for The Spiders for Bob Gardner. There was to be an extensive falling out, a stoochie, whether generated within the club or perhaps by international defeat in early March 1873 in London, where England played 1-1-2-6 and Scotland 2-2-6 once more, is unknown. But by October 1873 Gardner's friend, Wotherspoon, had moved the mile or so across to equally near neighbours, Clydesdale, to be joined later by Gardner himself. A "J. Gardner" plays there at full- or half-back on 15th November behind Wotherspoon, as had a Gardner for almost equally nearby Dumbreck nine months earlier, but that may be, rather than a mistake in the initial, simply another withthe same surname or even Robert's elder brother, James. An R. Gardner definitively first plays between the sticks and as captain on 13th December, by when the Titwood Park club, having previously again played English-style had adopted 2-2-6, as, whilst Vale continued with it, had Granville and another and still newer club was seen from the start to be using it too. It was Renton.

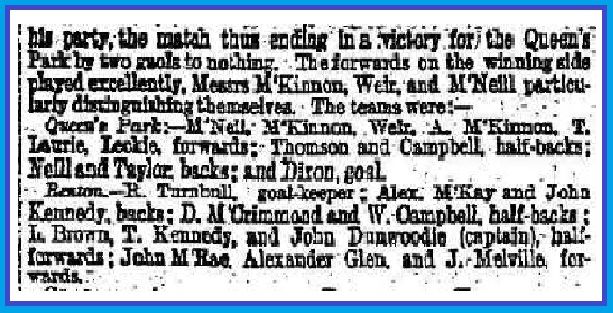

Whilst Renton F.C. was clearly not in the absolute first wave of Scotland's football clubs (it had not been a founder member of the SFA) and its actual foundation-date is un-known it was one of the entries seven month's later into the first Scottish Cup. Moreover, at that initial attempt it would reach the Quarter-Final, losing only to Queen's Park, the eventual title winners, 2-0. Furthermore it would do it with a team that we know in detail (see below), one which included, for later reference, a Melville and remained largely unchanged when the club would the following year go all the way to the final, held at the first Hampden Park and won by the home team once more, this time 3-0.

But here again there is something else that is, if anything, more worthy of note. In that December 1873 encounter with Queen's Park both teams lined up as notionally 2-2-6 but in a contemporary report in The Scotsman no less more detail of Renton's positioning is given.

Alex McKay and John Kennedy were the full-backs, McCrimmond and Campbell the half-backs. But in front of them were three "half-forwards" and beyond them three "forwards". In other words there were firstly three pairs and secondly they were not horizontal across the pitch but vertical. The Renton formation was actually 2-2-3-3 and still more to the point, like the block-four defence, the term "half-forward" comes straight from Southern shinty with full-forwards in front of them. In other words Renton was observed as a first playing football using an almost fully Southern Camanachd formation that retained the full-centre (see again above), added another but was, in order to reduce to eleven players, less the two wing-centres. Moreover, the horizontal to vertical adjustment clearly worked, with more to come and the following implications. From these new tactics and not known passing, used in any case for two millennia in the ancient game, would rapidly emerge, perhaps via 2-2-2-4 with centre-forwards side-by-side at The Vale, a, in fact THE, distinctively Scottish style of play, which can and in both parts be seen almost as quickly to be adopted by other teams; even if Queen's Park proved to be one of the most tardy.

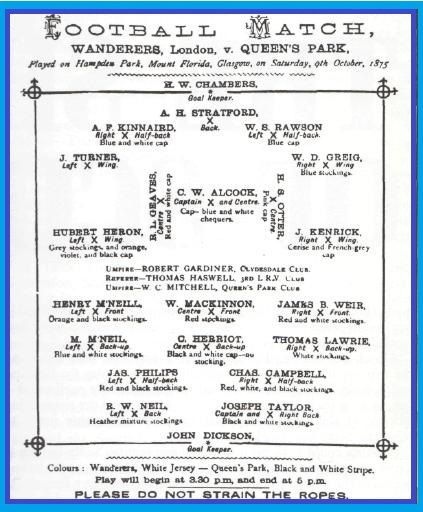

The earliest reporting of it and vertical forwards would be on 9th October 1875. It was versus The Wanderers once more and this time with both a certain Arthur Kinnaird and also Charles Alcock in the Londoners' line-up. For Queen's Park Lawrie, in front, and Weir were on the right, McKinnon and Herriot in the middle, front and backup respectively, and similarly the McNeill brothers, Harry, a known shinty-player, and Moses, on the left. FYI Queens at home at Hampden won 5-0.

At this point Queen's Park had been and would remain undefeated. But that was to change and it was to be The Wanderers, which were first to make it happen. In the follow-up friendly to the above game and four months later in February 1876 they back in London would be victorious by 2-0 but then Queen's Park, playing essentially with ten men, had something of an off-day, rectified with a 6-0 win away against the same opposition in November that same year. However, that was to be just seven months before invincibility in Scotland also came to an end. It happened on 30th December in the Scottish Cup and at the hands of Vale of Leven. It had, after the Ferguson affair, essentially seen elimination from the first two Scottish Cups, but had been building up a head of steam. In its first year it had gathered a pool of twenty-four or so players that was then reduced over three seasons to a squad of sixteen to twenty, Ferguson included; one which essentially knew each other's game. They were drawn from the same calico works that had previously supplied the shinty players. In fact, a number of them were also accomplished at the game. And they would soon constitute the World's first consistently successful, working-class club. Renton, equally if not more working-class, had had its moment first but, having just eliminated Scotland's previously unvanquished doyen, The Vale would not only take that Scottish Cup that year and but for two more consecutively after that and in 1878 in beating the English FA Cup holders, The Wanderers once more, be ipso facto the first best club in the World.

(Here the work done at Stirling University, as shown in Scottish Football Origins, in examining the back-grounds of the players from the Vale of Leven, including Dumbarton, from the valley's three main teams, makes the point far better than we can.)

That is, however, not to say, meantime and a mile and a half down the road Renton had been just a one-off wonder. It too was prospering. Whilst in 1875-76 it had been knocked out of the Scottish Cup in just the second round and by The Vale it not only had an established group of players but one which it was able to re-build still from local talent. And, although it would in 1876-77 be eliminated in round one again locally by Dumbarton, in 1877-8 with the new squad it too would find a wave, one of its own, making it all the way to the penultimate round and only lose to Third Lanark on a replay, this as The Vale had been granted a semi-final bye. Who knows how it might have turned out had it been the other way round but it is not inconceivable, as Renton was about at last in Tontine Park to have its own, proper ground, that first, the final would have been all-Leven and, second even, that Renton might in winning have gone on instead to become both Scottish and Scotland's already second World Champions. Such are the fine margins of footballing fate."

"The Absurdity of the Parochial

At the beginning of the month (sic) an excellent report on some origins of the beautiful game was put out as a news item on television. It is neat, slick and informative and can be seen by cutting, pasting and clicking on (No Longer Available):

Birthplace-of-football-shares-its-history-in-bid-for-heritage-status

But it is also disingenuous because it seeks not just to connect but also deliberately to confuse "Foot-Ball" and "Foot Ball" with what we play today, the Association Rules game. The item was on ITV, English ITV. Its source was Sheffield, from where in recent years has come laudably deep and important research on the former locally-played, Sheffield Rules version of the game and now has emerged a campaign for UNESCO recognition of it, seemingly, as the sole place of origin for football in its modern form.

Now it might seem to be dancing on a pin-head but, as with the article above on the SFA not knowing where it started (NOT INCLUDED), accuracy matters. So let us try to impart some. There were four stages, all in Britain, to the initial creation of what is today's football.

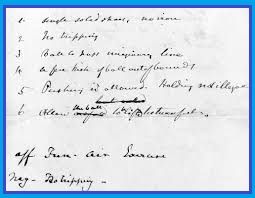

The first was the local, ad-hoc mass games what we in Scotland called "fitba" but existed through these islands. The second was the foundation of the first "Foot-Ball" clubs (note the hyphen) with codified and written rules. There is an argument that this first took place in Scotland in Edinburgh in 1824, lasted until 1841 with one copy of its hand-written rules shown as an example.

Then, third, there are the Cambridge Rules, of which there were several iterations, with the printed 1856 version illustrated. But note two things. First, the iterations did not flow on one from another. They seem to have been separate codification attempts with differing drivers. Second, they were, as illustrated, for a "Foot Ball" club, no hyphen, and again subject to change and addition, not least in 1861 by the Forest Football Club, later to be known as The Wanderers and future five-time Football Association Challenge Cup winners, the FA Cup including its first playing.

And finally from 1857 there is Sheffield, where a vibrant club culture developed, it is claimed from 1859 with the publication of its rules but in reality in the next decade with the foundation in 1860 of Hallam, Sheffield F.C.'s first external opponent.

But back to the pin head. "Foot-Ball" and even "Foot Ball" are not "football" as we understand it. They weren't in Edinburgh or Cambridge. And they did not become so In Sheffield either and to pretend otherwise is unhelpful. Not just are Sheffield's printed rules for a hyphenated game but the ITV piece's filming of the ledger of the founder of the first Sheffield club shows it clearly referring not to football but still "foot-ball", with a hyphen as in 1824. The transition had not yet been fully made.

So where does this leave us? After digitalisation much good work by many in many places has been done not just to uncover the real origins of modern football but also to sweep aside a number of myths. The fact is that the proto -game in Britain developed in largely parallel in a number of locations in these islands before coalescing. London produced an initial set of rules that stuck. Sheffield added and considerably improved them when in 1877 it merged its FA with that in London. Scotland, as its results show, provided tactics and technique. That it happened should be celebrated. However, instead there is parochialism and it is absurd. Where we have been allowed by technology the opportunity for clarity and agreement attempts are being made to create new but equally tenuous myths and resentments - North England of South England, Scotland of England and vice versa, even Scotland of Scotland - are not being eliminated but instead reformulated. A halt would be good."

_______________________________

____________________________

"Stranraer - and the Coming of Football to Scotland

Perhaps one of the most remarkable stories of the coming of football to Scotland, and one of the least known, is that of Stranraer. Founded officially in 1870 it is the third oldest club in the country. Only Queen's Park and Killy (Kilmarnock F.C) officially predate it and even then there are doubts, for which we have to thank not SFHG research but a unique piece of work, The First Thirty Years, preserved on the Internet from 2002 and by a John Boyd, of whom nothing more is known just yet.

In it he states that already by 1865, two years before Glasgow could even have heard of Queen's Park, Stranraer, The Toon, already had three clubs - Lodge, Sheuchan Swifts, Sheuchan, being a main street to this day, and Waverley, Waverley Lane being another - and perhaps even a fourth. Moreover, that same year a recorded game was played, 11-a-side, presumably to some form of agreed rules, away against Cree Rovers in Newton Stewart. It was made possible by the new-fangled railway and was not only with a clearly organised, representative "town" team but one for which we also have the on-field line-up. And that was a dozen years before Stranraer F.C. first entered the Scottish Cup in 1877, to be beaten in the First Round 6-0 by Queen of the South Wanderers, and a three-quarters of a century before it joined the League, with many a game played in between. They included a second early one, in about 1870, as also the three Toon clubs combined, this time versus the 3rd Kirkcudbright Volunteers at Palmerston in Dumfries, and 1875 against Cree once more, for both of which again we have knowledge of those taking part.

In 1865 in goal was Cluckie. Then there was Warren and Simpson, Bell and T. Alexander. The captain was McQuiston and he was said to be joined by R. and G. Porteous, Craig, Nish and a second Alexander, P. . Furthermore, with amazing continuity, Cluckie remained in goal in 1870 as, in the wider team were also Warren and Simpson, Bell, now J.B. Bell, McQuiston, still captain, Nish, the Porteouses, one, Robert. And the eight remaining were joined by Mackie, Fraser and Mckinstrae. Moreover, even in 1875 both Warren and Bell were playing on still.

However, between 2002 and now something has changed and that is the explosion of the Internet itself and, more-to-the-point, the availability of resources on-line, notably ScotlandsPeople and similar. It has meant that we can look for and at the names of provided in the line-ups, specifically in the 1861, 1871 and 1881 censuses and for males aged between, say, fifteen and thirty. The results show almost all appear in Stranraer itself and surrounding nearby villages. And with some of the names we can even be more specific. A McQuiston was twice the captain and, whilst no-one of that name appears on the local record, there is one in Glasserton and it is an Ayrshire, most specifically an Ayr name. So where had he learned the game? Futhermore the Cluckies and Porteouses were Leswalt and Kirkholm people. And then there is Bell, J.B. Bell, a stalwart of the local game for at least a decade, and here we have perhaps a specific candidate - John Bell, recorded with a middle-name of both Broadfoot and Bradhurst. He was born in 1848 in Stranraer, so was seventeen in 1865. He became a joiner to trade. In 1871 still in the town he married Isabella Boan, who actually lived on Sheuchan St. at the time, although he gave an address in Glasgow. And it was there in Govan from 1872 that all their five children were born and from where by 1881 they all disappear from the records.

But the question remains, how and why was football, but not necessarily yet the Association variant, played so early in Stranraer and indeed Newton Stewart and Dumfries? Where did it come from? And answer there is as yet none. Unless it, as the Anwoth story (See above left) from two hundred earlier tells us, it was and remained indigenous.

In fact the nearest we come in South-West Scotland to any connection is the private work done by the laudable Richard McBrearty of the Scottish Football Museum and posted on his personal blog, The Origins of Football in Scotland. He states that John Douglas, the Marquis of Queensberry, and incidentally father of Lady Florence Dixie, later the first sponsor of the women's game , returned to his Kinmount estate by Annan from Cambridge in 1866. And that same year he set up under Association Rules, Kinmount F.C., which in itself is literally game-changing because Queen's Park by a year then ceases to be the first "soccer" club in Scotland. Furthermore, three more teams, Annan (formed 1867), Springkell (before 1870) and, importantly for the purposes of Stranraer, Dumfries (1869/70) then by the end of the decade emerged to join Kinmount, with games played in 1868 between it and Annan, presumably to FA rules-ish but 15/16-a-side, the first at least with the Marquis in the team and scoring.

_______________________________

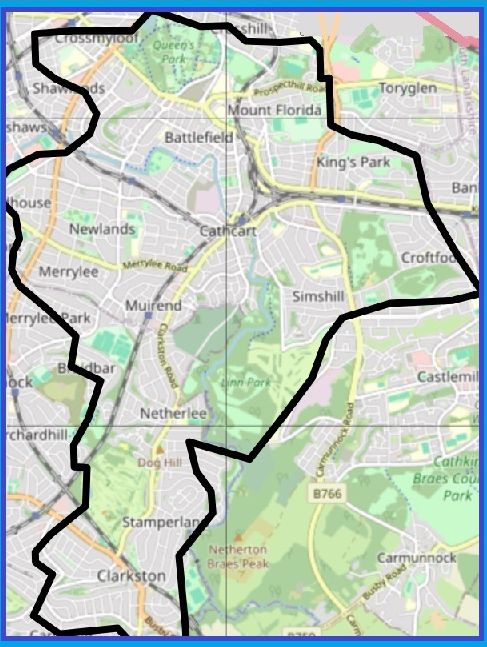

Cathcart - the Cradle of Scottish Football

(and a bit of English etc. too)

Cathcart, once in Renfrewshire, now in Glasgow, is both a village-suburb and a parish. This piece incorporates the former but is about the latter, from almost the Clyde in the north to nigh-on Busby in the south, Linn in the east and Crossmyloof or so to the west, and the role it has played not only in cradling football, our football, Association football in Scotland, but creating it elsewhere, the former so obviously continuing to be played today, the latter having been pivotal to the global game, notably in England, Uruguay, Brazil and, to a lesser degree, Argentina.

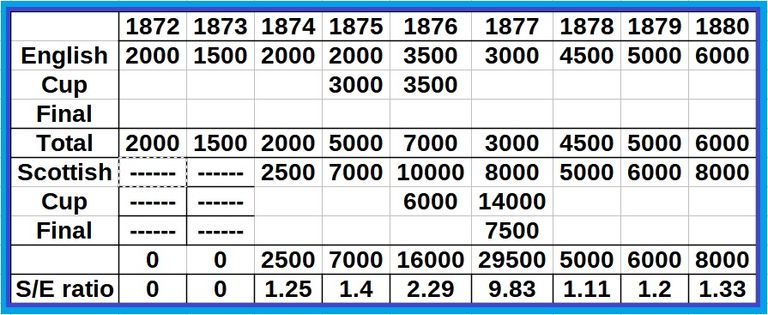

The birth of our football in Scotland, not the Scottish game itself, in reality took place on the last day of November 1872 and at Hamilton Crescent in Partick, also then not in Glasgow. That would require another forty years. And it was there for a reason, one quite possibly decided upon, indeed hatched at the Queen's Park Football Club in Cathcart but needing to be implemented elsewhere because the parish had no suitable venue; at least not quite yet. The first Hampden Park, in part now Hampden Bowling Club, would not be opened until the following year and become an international ground only in 1878. Although in 1876 it did host the replay of what might rightly be called the Cathcart Cup Final between its owners, Queen's, and its nearest neighbours, the now defunct Third Lanark; its ground, the first Cathkin Park in Crosshill and just half a mile away. Indeed, the second Hampden Park, in what we now call Cathkin Park after the original, would from 1903 to 1967 also become the new but second stadium of The Thirds, having been used by Queen's from 1884 until 1903. For it was then that the earliest version of what we now know as The National Stadium was completed on Mount Florida with beside it the fourth or Lesser Hampden, known previously as Clincart Farm, now as The City Stadium and from this, the 2025-6 season, the latest home of the club, the doyen club that had made it all possible.

For it is almost, stress almost, axiomatic that without Queen's Park, the club, there might well be no Scottish football. The club would be the fulcrum through its acceptance in 1871 of the rules of the Football Association in London and its willingness in the early days to apostolise and demonstrate the game wherever it could. Moreover, its participation in the semi-final, albeit in very advantageous circumstances, of the first (English) FA Cup and then provision officially of the entire Scotland eleven in 1872 for that first and drawn international were the sparks that set alight what, North of Border at least, flamed into a special passion for the game that even today persists.

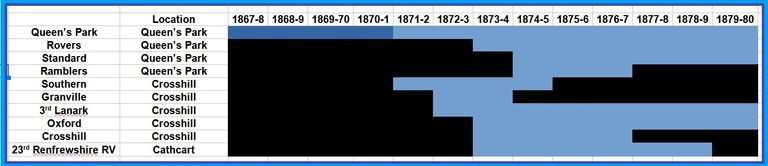

The facts are that within five years of Queen's Park's emergence as our game's doyen club the park itself became the home of sixteen further teams and within a stone's throw there were the grounds of nine others.

(Lighter blue indicates playing Association rules, darker blue not Association, black means club not in operation)

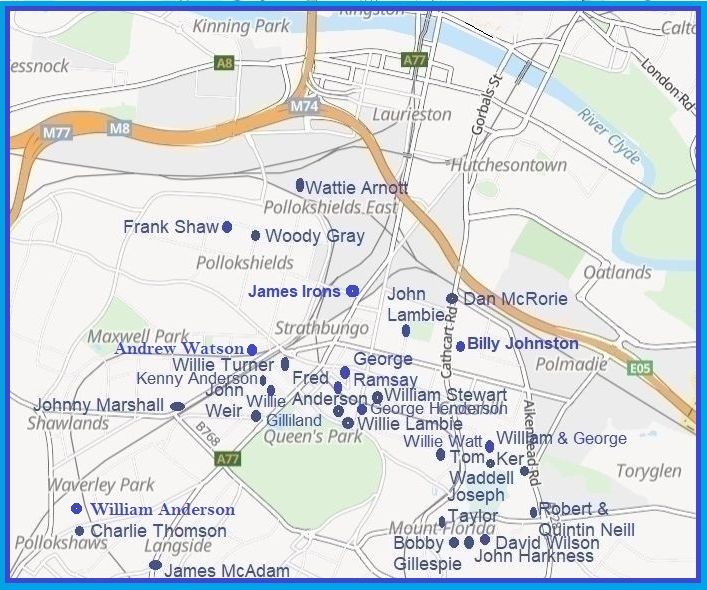

Furthermore, within a radius of a mile and half or so there would teams in addition. And all were formed by and not just needing players but also producing many of them very locally with the concentration over the years of just the best or best-known of them there to be seen.

And already by the middle of the 1870s Cathcart players were having their effect elsewhere, as was passion also spreading out. In 1876 George Ramsay, having played for two of those local teams, Oxford and Rovers, had taken himself south to Birmingham, there almost immediately to be instrumental in the creation of Aston Villa.

And nor does Cathcart's influence on Britain's major clubs end there. In 1895 Sheffield Wednesday won the FA Cup. At inside-right was Alex Brady, considered to be one of the three or four most talented Scottish players never to have played for his country, but unlike the others not because, whilst being raised a Scot in Scottish football, he had been born in England. He had been raised in Renton, learning the game there, but he had been born at Burnbank by Cathcart station. His father was a cotton dyer, who had worked at the mill there before finding similar in the Vale of Leven. And the reason for Alex never pulling on the blue jersey - aged sixteen he was so good, an early Pele, and already at the start of, including one at Celtic but also Down South, a sixteen-year, professional career, for ten of which he was by the rules of the time ineligible.

And so to Celtic itself. It is said that on a December evening in 1887 a small group of men chapped on a door on the Clarkston Road in New Cathcart. One was a priest, Brother Walfrid, the founder of the club, another John Glass and they had come to try to sign the eldest son of a Drill Hall sergeant and already a Partick Thistle player. He was Tom Maley. But he was not home. He was out courting the girl he would later marry. And so the story is that instead of Tom his younger brother, Willie, was recruited, and from Third Lanark, not instead but in addition because both brothers would soon take the field for the Parkhead club. Tom would for several years successfully play as an amateur, whilst also teaching, before going on to manage Manchester to the FA Cup in 1904 and Bradford City into the top-flight. Willie would have a decade in Glasgow's East End as a player, win three Scottish caps he should not have (because he had been born in Ireland), from 1897 manage The Hoops for forty-three years but in death in 1958 remain true to his South Suburban roots. He is buried in Cathcart Cemetery.

And it is to Cathcart cemetery, that we lastly turn. It is beautiful, a place for a tranquil walk, but sadly far from immaculate, yet if there is world-wide a more important resting place for football’s early movers and shakers we have yet to hear of never mind see it. It is, including Willie Maley, the last resting-places of at least 19 of Scotland’s greatest players, pre-Second World War and others post, notably Tommy Burns. Nine more were cremated at neighbouring Linn Park. It contains lairs of footballing ambassadors, administrators and managers too. From the earliest days there is the grave, restored by his family, maintained by us, of Joe Taylor, Scotland’s first full-back. Wattie Arnott's has been restored also. Hugh MacColl, the captain of the winning team in the first, officially-recognised football match in Spain is there, Toffee McColl too, amongst others, as is Rangers first manager, William Wilton. George Pattullo has a memorial. He, when playing for Barcelona, had a better goals-to-games ratio than Lionel Messi. And there are others, all of whom lie in area of 500 by 300 yards on the southern edge of a concentration, the cradle of footballing pasts and presents two thirds of a mile by half and all within a larger catchment of over half a century of players to Scotland, Britain and the World little more than two miles by one.

______________________________

The Dunbarton Leven

- Source of the "Scottish-Game"

In November 1872 something happened. It was the World's first Association football international, in Glasgow but expected to be something of a walk-over for the away-team, England. It proved, thanks to intra-club familiarity, some with-ball talent and the nous and organisational, read tactical, ability of the Scottish captain on the day, Robert Gardner, a little different. It was also the catalyst for the creation of four specifically Association football teams in Dunbartonshire along the banks of the River Leven that flows the five miles from Loch Lomond to The Clyde and then more clubs elsewhere; by less than a year later at least sixteen in all.

In the meantime four more games had taken place, all important. The first, it is reported, had been on 21st December 1872, the second on 11th January 1873, the third on 15th February and the last on 1st March, two in Glasgow's southern suburbs, two not and all between the same two teams, Queen's Park, Scotland's doyen, and Vale of Leven F.C., The Vale. The first and last would be wins for the former, but the middle two, the younger club clearly learning fast, certainly in defence, were goalless draws.

More games followed after the summer-break, not least now with the instigation under the auspices of the almost equally new Scottish Football Association of the first Scottish Football Association Challenge Cup, the "Scottish Cup". But The Vale was not to be there. Its second nearest and neo-contemporary neighbour, Dumbarton, had accused one of its player of being that heinous thing, a professional. It was a try-on. The player in question, Johnny Ferguson, at twenty-four an old man in a young man's game but who nevertheless would become football's working-class star, had won prize-money only for running. But it was a stoochie, despite Ferguson nevertheless in the meantime being chosen for Scotland, that, at club level at least, would take two years properly to resolve. So Queen's Park found itself in December 1873 in the semi-final meeting Renton, the third of four brand new Vale of Leven's clubs. It had eliminated Dumbarton in the previous round and just now would be eliminated itself.

Thus there were by October 1873 already three obvious clubs in the Vale of Leven, five with second and third Dumbarton club, Alclutha, later Dunbritton, and Lennox also there in the back-ground. And that later in the year would become seven, three now in Alexandria with the addition of Star of Leven and Vale of Leven Rovers, both. The former would last a decade, the latter at least four seasons. Both would never get beyond the Cup's Second Round. But Renton, with The Vale effectively still excluded, had done so for a second time. In fact in April 1875 it was to go all the way to the final, there, having kept it scoreless for more than an hour, to be beaten and by Cup-holders, Queen's Park, once more.

It was all very encouraging and in 1875-76 enough for a further club, Renton Thistle, formed also in 1873, the eighth to join the fray and from Queen's Park Juniors receive a walk-over into the Second Round. Moreover, finally unhindered by accusation The Vale would get to that same next round after walking-over Vale of Leven Rovers. And it would be both The Vale, via Renton and Mauchline and Dumbarton via Renton Thistle and a bye that would make it to the semi-finals with, however, neither making it further. The Cathcart combination of Queen's Park and Third Lanark contested the final that season.

But there had been successes elsewhere and more to come. In March of 1875 in the Cup semi-final eventually won by Queen's Park it had conceded its first goals ever, to Clydesdale and a brace. Indeed it had had to come from behind not once but twice. Then in February 1876 it lost its first match, 2-0 in London to the Wanderers. Reasons given were that because of injury they essentially played with ten men and interestingly the pitch had been narrowed, the home team clearly wanting to constrict the visitors' game. The question is why. Was it to restrict passing. And finally in December 1876 the Hampden team lost its first game to Scottish opposition. It was in the Quarter-Final of the Cup, it was at home and to The Vale, the last survivor of seven Leven teams that had in September entered the competition, Queen's Park having held the lead at half-time.

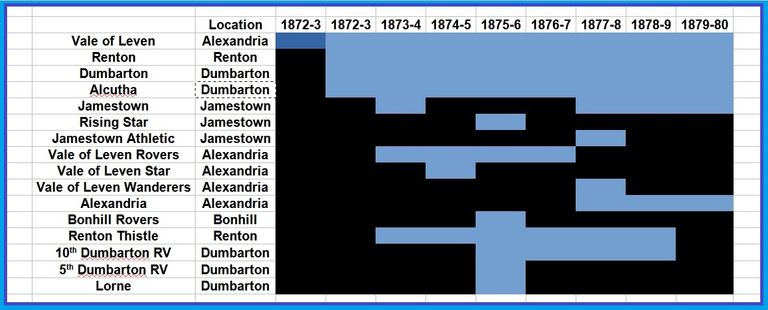

The game had and would not be without controversy, as would the Final also, one which The Vale would go on to win via two replays and a remarkable 35,000 being thought to have watched the three matches in total. But it marked a trio of things. The first was Queen's Park as a team was fading and would not be a driving-force in the Scottish game for another three seasons after it had actively recruited to rebuild its playing-strength. The second was that The Vale was the coming-team and would be that driver for those same three years. It would have a three-in-the-row of Scottish Cup wins in a row and do it with a combination perhaps of greater fitness due to its players' working-class lives but also because of positional innovation in attack and then team-linkage. The six forwards would become notated in pairs, first across the pitch, as a 2-2-6, and working in combination, and then vertically as 2-2-3-3 with the origin being quite possibly shinty, the winter game played along the Leven from its source to its mouth before the Association game and then still practiced. And, thirdly with eight teams in the 1877-8 Cup with the addition of newly-founded Alexandria, based around the town's cricket club, then Jamestown, formed in 1873, joining the following season to make ten vying for the trophy - fourteen clubs in all with the 5th Dumbarton RV, Jamestown Athletic, Bonhill Rovers and Vale of Leven Wanderers - the baton could and would be passed around and on locally.

(Lighter blue indicates playing Association football, darker blue not Association or not all season, black means club not in operation)

In fact it was so local that today between Jamestown and Dumbarton it is just twelve minutes in a car. And with it In 1879-80 Dumbarton, having eliminated both The Vale, in a seven-goal, First-Round tussle, and Renton on the way, would reach the semi-final only to be beaten but a single goal in the second half by eventual champions, a re-emergent Queen's Park.

And thus it seems there is a more than adequate argument that a coherent, distinctive style of very successful Scottish play, began to emerge not so much from Queen's Park to 1876 but to 1880 under The Vale, with it being adopted by the other Leven teams, also by the "new" Queen's Park, by West-Central Scotland at least, Edinburgh going something of its own way with its earlier adoption of the Welsh developed 2-3-5, and by the Scottish national team that would not lose a game in a decade. And that distinctive style is again reflected in the almost complete dominance of the Scottish Cup by the Hampden club and first two, Dumbarton and The Vale, and then three Leven clubs for the next seven campaigns. And this may have been longer still had that third, a re-emergent Renton, and Leven clubs more generally not been, as in the case of the former, "raided" by a nascent Celtic and then the collective "pillaged" by clubs Down South, Renton having from 1884 developed and in 1888 revealed, indeed unleashed, a final ingredient to the mix, the Scottish Centre-Half; the Pivot, it taking that distinctive and repeatedly successful football already played in Scotland from a "Style" to a "Game", arguably eventually the World Game.

It meant that in a rapidly changing football scene on both sides of the border as the source was effectively drained to dry only Dumbarton has survived long-term and then with a gap. Alcutha from that same town are long gone as major teams, as are Jamestown, Alexandria's Star of Leven and Vale of Leven Rovers, Renton Thistle too, and, of course, The Vale and Renton them-selves. But absence does not change the facts.

Known Renton, Renton Thistle, Vale of Leven and other Upper Vale Teams

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

- N/A

1872-3

_________________________________________

- Cunningham

- Wylie

- Fergus

- Ferguson

- MacDermid

- Moodie

- Graham

- McKechnie

- MacDonald

- Lang

- Edmunds

1872-3 - Jamestown

_________________________________________

- Robert Parlane

- Archie Michie

- J. M. Campbell

- James White

- John C. McGregor

- George McGregor

- Robert Lindsay

- Robert Jardine

- J. McNichol

- John Ferguson

- J. Campbell